Secretive vendors are exploiting a free money glitch in the U.S. healthcare system

BlueCard underpayments are the latest example of healthcare vendors making money from complexity

A group of secretive vendors is exploiting a loophole in the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association (BCBSA) network to make tens of millions of dollars per year, often at the expense of patients.

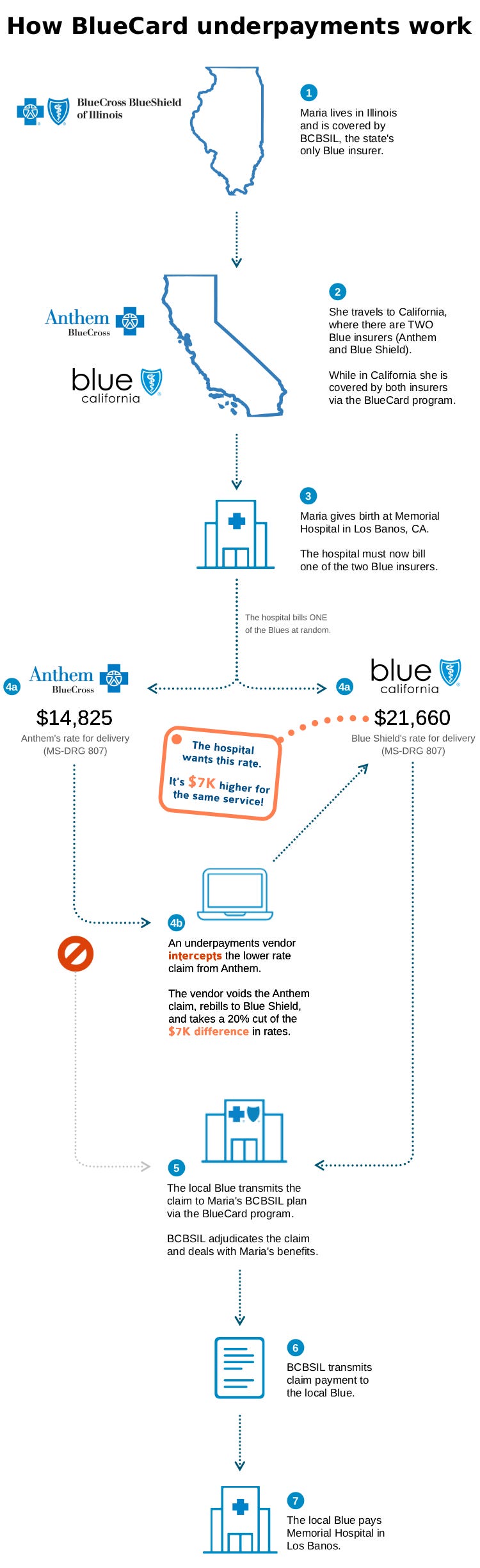

The loophole, known as BlueCard underpayments, involves arbitraging prices between different BCBSA-affiliated insurers located in the same state. The process is obscure and works in just a few states under specific conditions. However, it can be incredibly lucrative for both vendors and providers, netting them thousands per patient encounter with minimal effort. Here’s how it works.

Most states have just a single Blue insurer – think BCBSIL or Florida Blue. However, some states have multiple Blue insurers (“Blues”). For example, California has both Blue Shield of CA and Anthem Blue Cross.

When someone with Blue insurance travels to a different state and receives medical care, that care is covered and reimbursed by the “local” Blue via the BlueCard program. BlueCard lets providers bill the local Blue instead of the Blue from the patient’s home state, AKA the “home” Blue. This decreases the complexity of billing for providers while making the patient's travel experience more seamless.

The trouble starts when a Blue-insured patient travels to a state with multiple Blues. In that case, the patient is covered by multiple insurers at the same time. Those Blue insurers may have different prices, even for the same service. After the patient receives care, providers typically bill one of the insurers at random, irrespective of price.

Whenever that happens, there’s an arbitrage opportunity for vendors. If the provider bills the cheaper of the two Blue insurers, a vendor can void or cancel the original claim, rebill the more expensive Blue, then take a cut of the difference in prices. Here’s the whole process visualized using real negotiated prices from California:

Providers are in on the process too. They contract with vendors to search for BlueCard underpayments in their recent claims, usually under the auspices of “underpayments recovery.” For providers, every rebilled patient encounter means more revenue. However, that extra revenue has to come from somewhere. Usually it comes from the higher-reimbursing Blue insurer, but patients can also get stuck with a higher bill depending on their cost share.

For vendors, this entire operation is a closely guarded secret – the equivalent of Jane Street’s India options trade, just at a much smaller scale. They’ve found a tiny gap in the system, a free money faucet to exploit for as long as possible before the Blues shut it off or the competition gets stronger. But the exploit isn’t really free; the cost is ultimately borne by patients, who end up with higher bills and premiums without even knowing they were used.

So today, let’s expose the whole thing. We’ll take a look at where BlueCard underpayment vendors are operating and what sort of procedures they’re targeting, then briefly talk about how the industry got here and why it’s likely to continue to face similar issues.

Where BlueCard underpayments actually happen

BlueCard underpayments are rare, even relative to the number of normal rebilled underpayments, and can only happen under specific conditions.

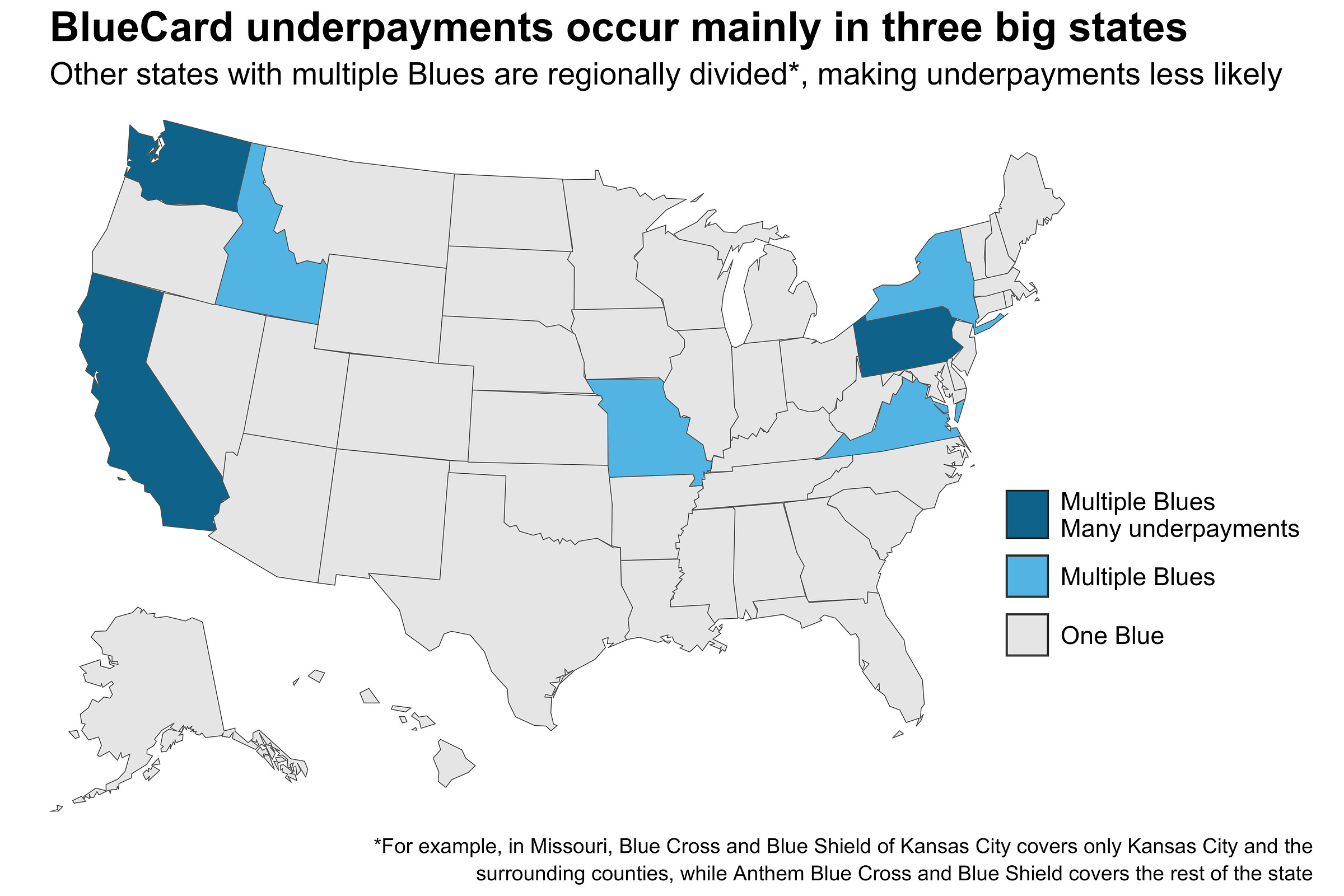

First, they can only occur in states with two or more Blue insurers, of which there are seven. Of those seven, only three are serious targets for BlueCard underpayment vendors:

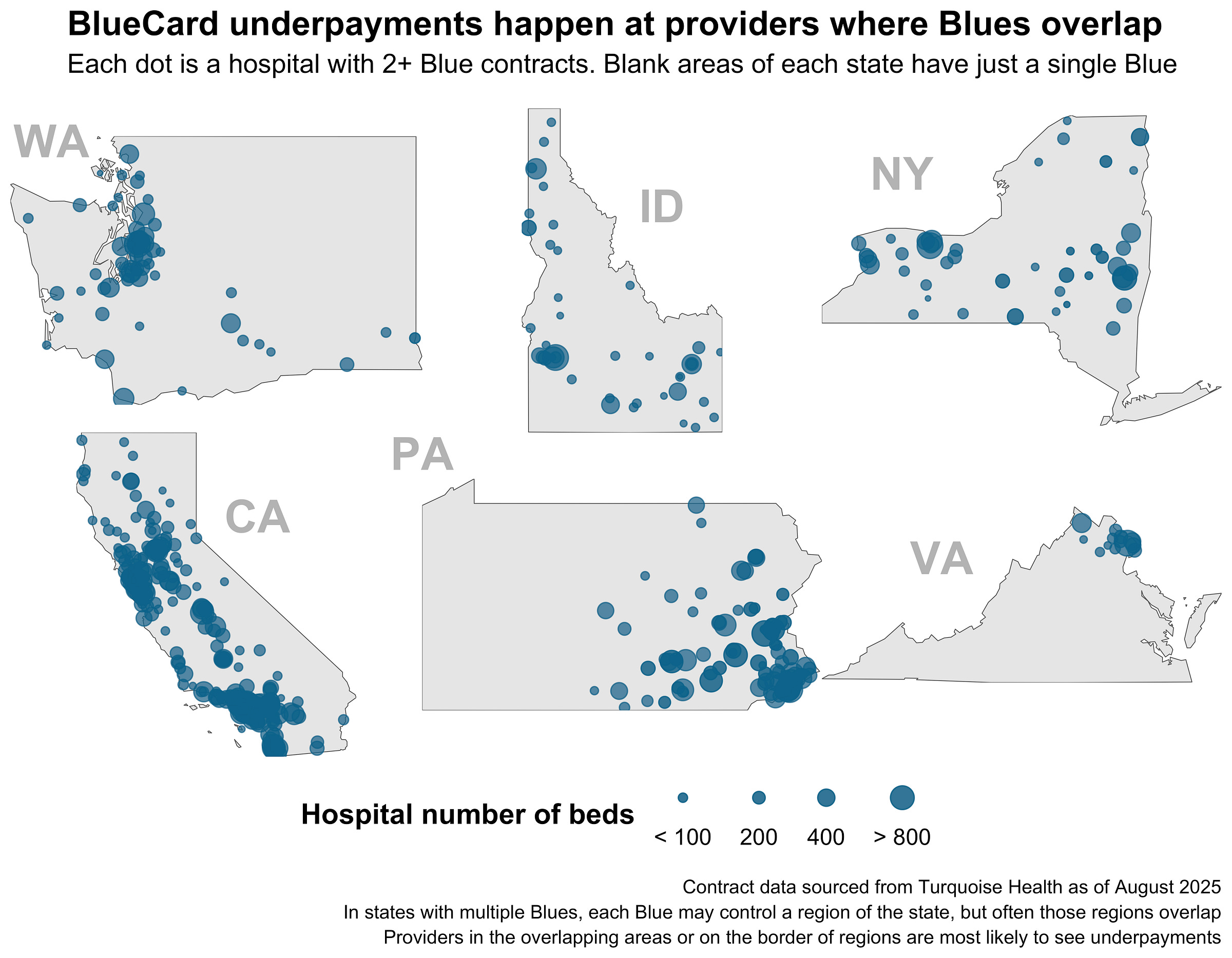

Additionally, in states with multiple Blues, each Blue may control its own region of the state. Below is a map of providers with negotiated rates from two or more Blues. Areas with many dots are regions where Blues overlap, while blank areas represent regions controlled by a single Blue. BlueCard underpayments can only occur in regions where Blues overlap.

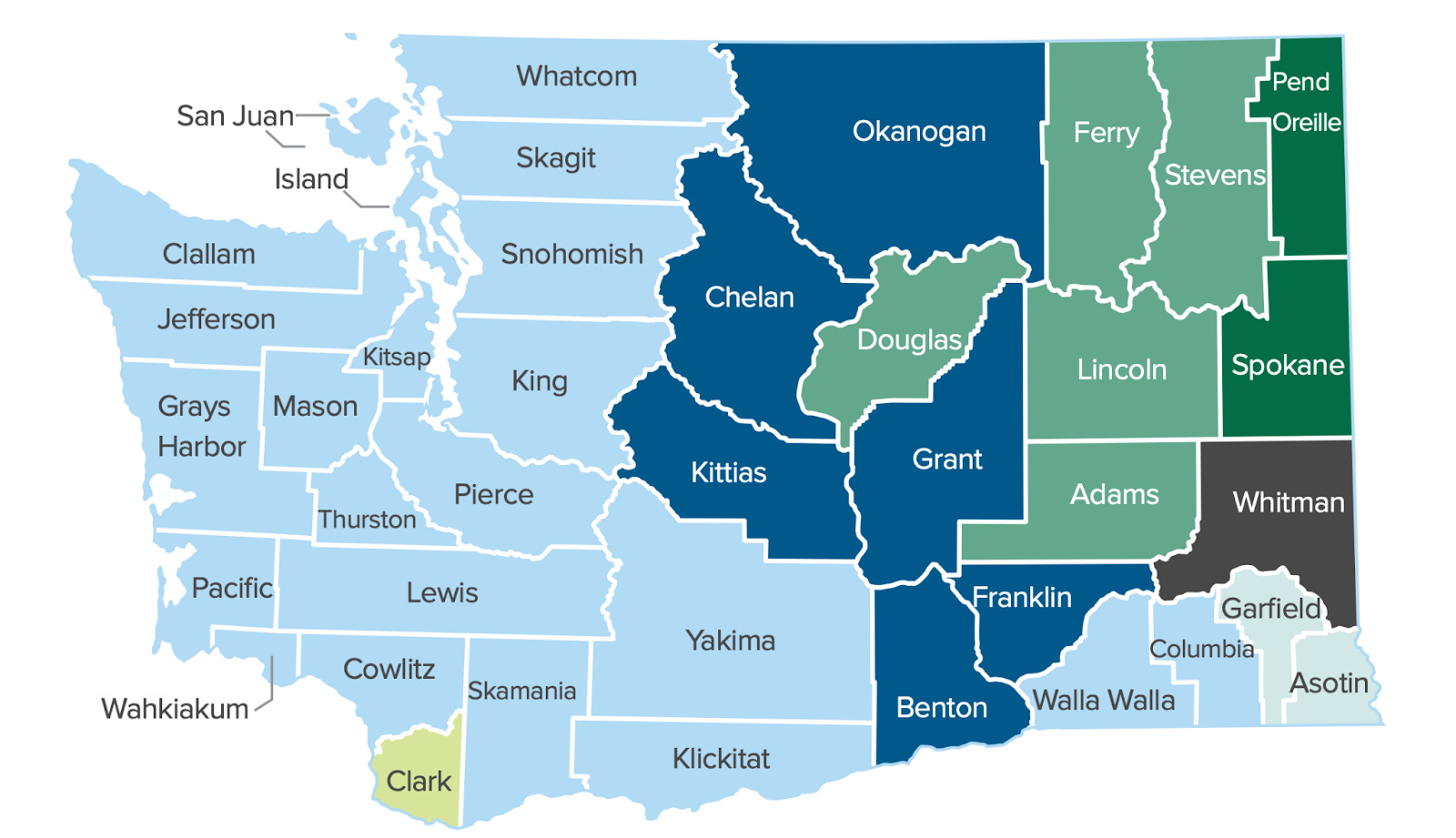

The regional overlaps get extremely messy. Here’s a map showing how just two Blues split coverage of Washington state. The light blue and green areas show the overlapping service area, while the other colors show permutations of coverage from different single Blues. You can see the light blue area roughly mirrors the area with many dots from the map above.

In other states, the situation is even more complex. New York and Pennsylvania both have four Blue insurers. Those insurers mostly don’t overlap, except in specific regions like eastern PA. Some states, like Virginia and Missouri, have just a tiny area where Blues overlap.

Further, whether or not BlueCard underpayment claims are even accepted is up to the local Blue insurer. Some don’t allow the sort of claim voiding and rebilling that makes the BlueCard scheme possible.

Finally, providers need to be in on the game. Underpayment vendors need access to providers’ detailed claims, contracts, and medical records in order to do their work. Providers grant that access with the expectation of getting additional, risk-free revenue from their closed or recent claims. In the BlueCard case, providers may tell their general underpayments recovery vendor to search for BlueCard claims, or they may contract with a BlueCard-specific vendor.

To summarize, BlueCard underpayments can only happen when:

A state has multiple Blue insurers.

Those insurers have overlapping coverage regions in the state.

A patient travels from out-of-state to one of those overlapping regions and receives care.

The local Blues allow BlueCard-style underpayment rebilling.

A provider in an overlapping coverage region contracts a vendor to find underpayments.

Although these conditions seem highly restrictive, several common scenarios make meeting them surprisingly likely. First, remote work has drastically increased the chance of someone being covered by an out-of-state Blue plan. Second, almost all of the multi-Blue states are economic or tourism powerhouses, making them likely destinations for travel or remote work.

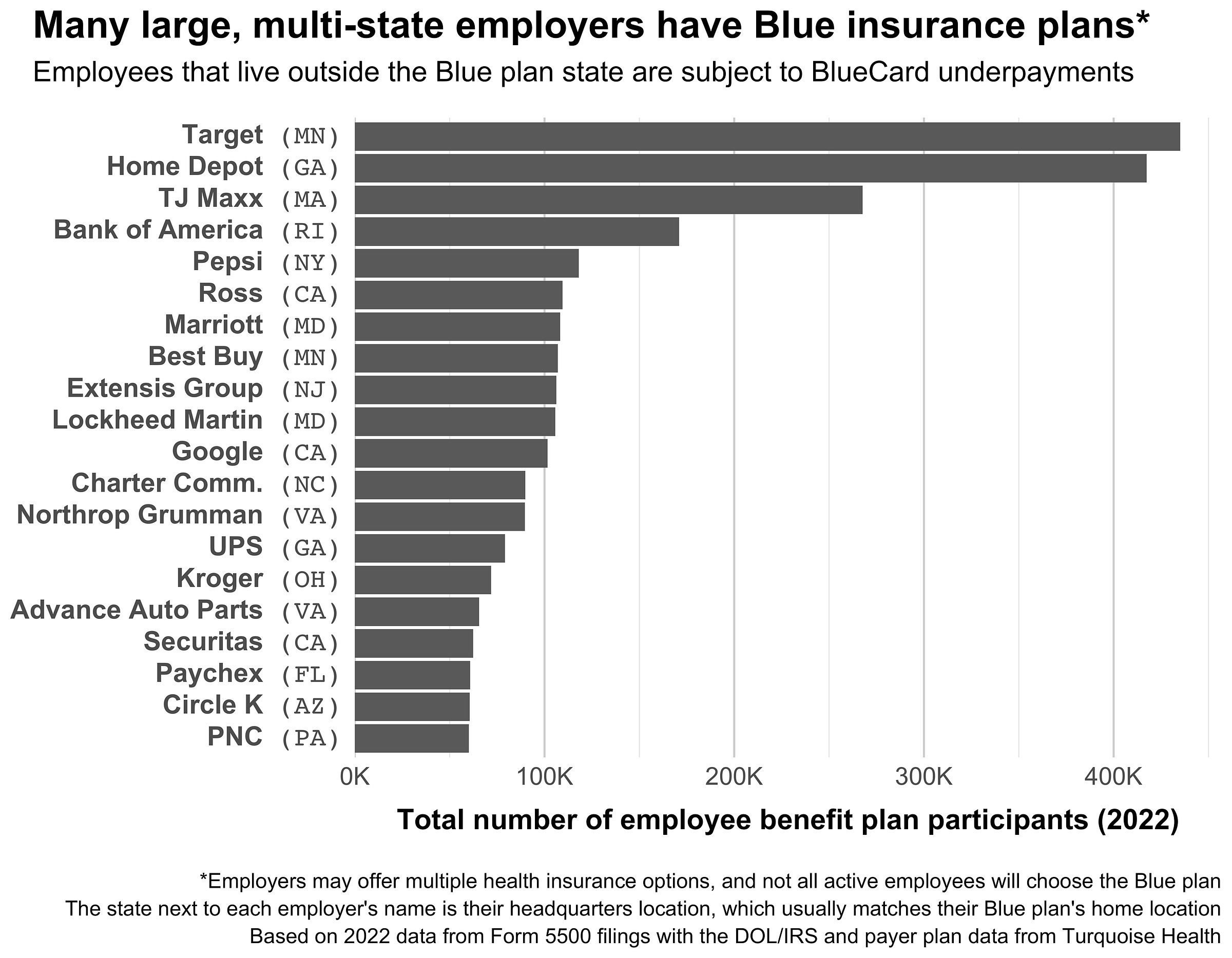

Third, many large companies offer a Blue plan from their headquartered state to employees spread throughout the country. In fact, the BCBSA requires employers to purchase coverage from the licensee in their home state1, regardless of where their employees are located. For example, Target has group insurance from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota and more than 400K employees in the United States. Here are the top 20 companies with a Blue plan by employee count:

Note, however, that not all these employees will have a Blue plan, as many large employers offer plans from multiple insurers (e.g. Target employees in California can get Kaiser). Further, some employer Blue plans require providers to submit claims to a specific local Blue. For example, in Washington state, Boeing (headquartered in VA) has an agreement that requires all BlueCard claims to flow through Regence, negating the possibility of underpayments for their employees.

Still, when you add up all multi-state employers with Blue plans, the scale is surprising. If even 1% of their employees meet the five criteria listed above, they’d likely generate hundreds of thousands of BlueCard claims per year, all subject to underpayments chicanery.

Vendors target the highest bills and largest rate gaps

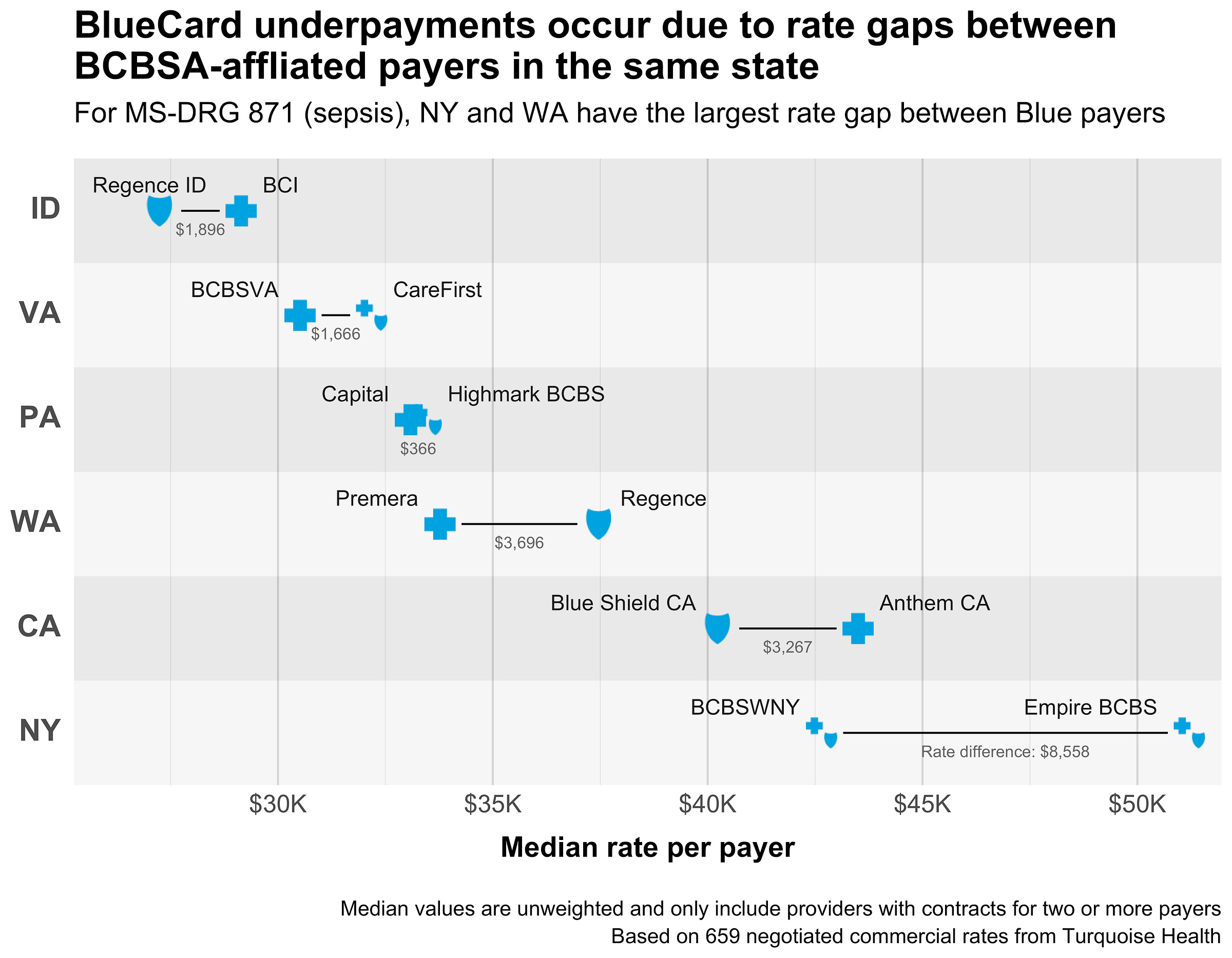

But vendors using this scheme don’t make money through volume (i.e. rebilling lots of small claims). Instead, they seek out expensive claims with big rate gaps between Blues. Those claims tend to be for things like long inpatient stays, surgeries, or complex treatments. For example, here’s the gap in median rates across Blues for MS-DRG 871 (sepsis with MCC):

Finding a sepsis rate gap like this might make a vendor a few hundred dollars. Not bad, but not huge money. Sepsis is also common, so pricing it is easier and the rate gaps for it are likely to disappear over time.

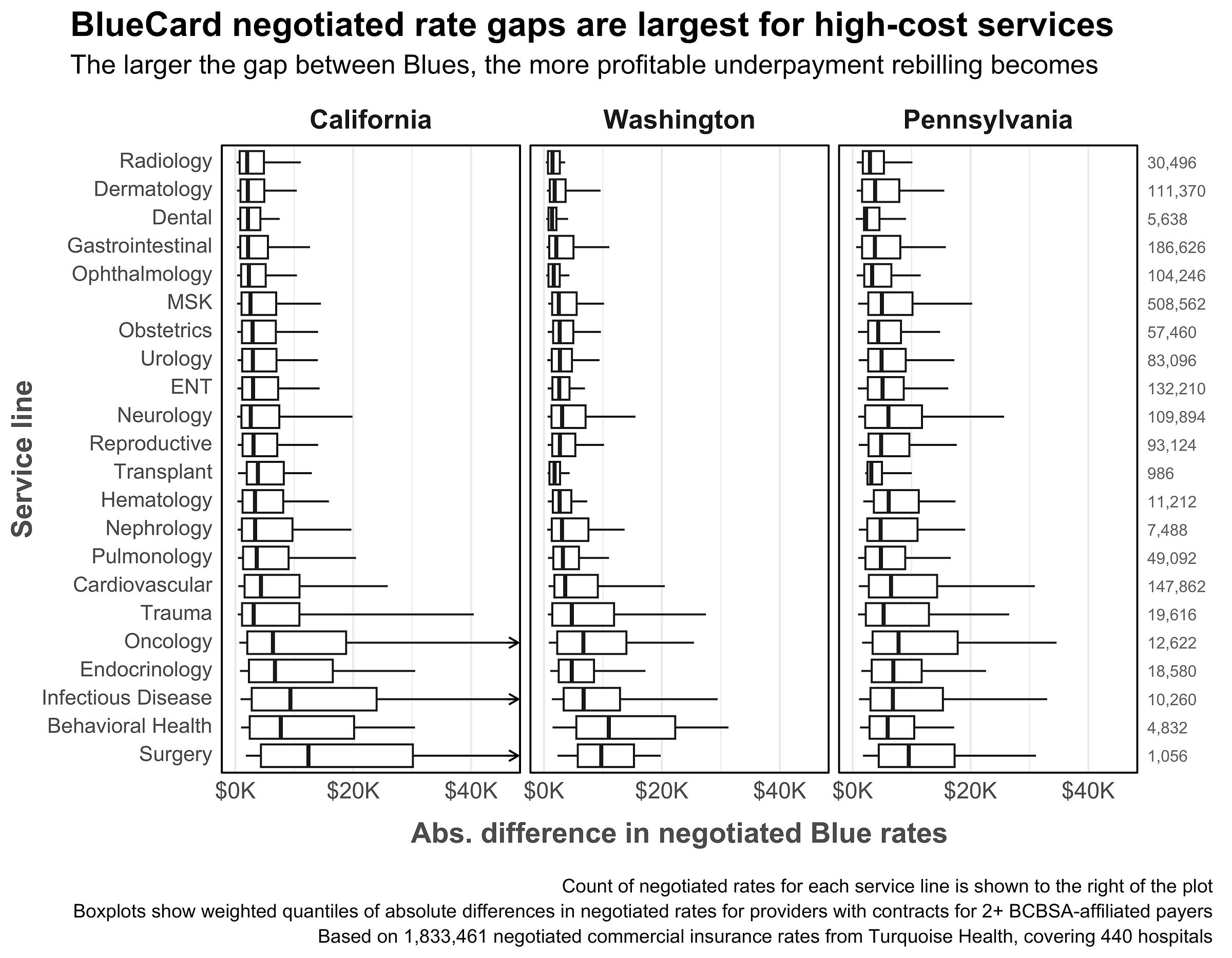

What vendors really want are the big, yet-to-be-closed rate gaps for obscure, expensive care. The plot below shows the distribution of rate gaps between Blues by service line in the three major BlueCard underpayment states.

Here you can see that services like oncology, surgery, and infectious disease treatment have the largest rate differences by far. For those services, the 90th percentile difference is around $45K, meaning a lucky vendor could make $9K on contingency (at 20%) for rebilling a single claim. And these gaps are just for single billing codes. Real bills could include multiple codes, professional fees, carveouts, and other complexities, all of which could have their own rate gaps.

In fact, the higher the complexity of the bill, the more likely it is to be scrutinized by underpayments vendors. The absolute juiciest targets in the BlueCard underpayments industry are stop-loss claims. These are claims where the cost of care exceeds a threshold amount and triggers a new payment methodology (usually percent of charges).

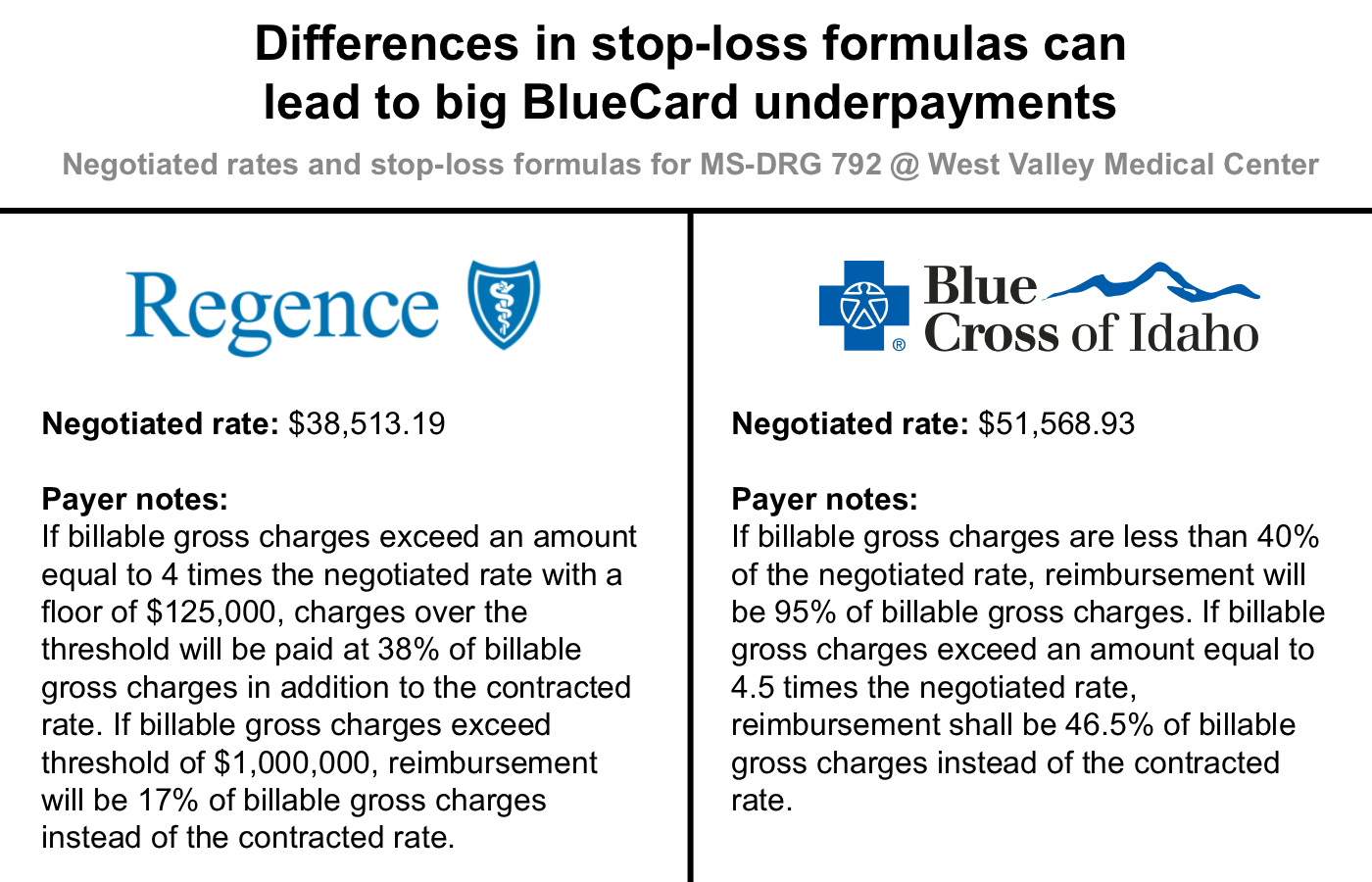

Stop-loss clauses are added to contracts to protect providers from the unknown cost of expensive, high-intensity care like traumatic injuries, major complications, and pre-term births. However, stop-loss payment methods/percentages can vary significantly by payer, creating huge opportunities for BlueCard arbitrage. For example, here are some real reimbursement rates and stop-loss clauses for a premature birth without major problems (MS-DRG 792) from West Valley Medical Center in Idaho:

In a normal case, Regence reimburses a flat $38,513.19 compared to Blue Cross’s $51,568.93, as seen in the Negotiated rate field above. The difference in those negotiated rates is big enough to arbitrage, but the payout wouldn’t be huge. However, in costly outlier cases, Regence has a much less generous stop-loss clause, meaning they would reimburse far less than Blue Cross and create a large rate gap.

For example, if a 2-week hospital stay generates $500K in gross charges, Regence would reimburse ((($500,000 gross charges - [$38,513.19 rate * 4]) * 38% of charges) + $38,513.19 rate) $169,973 compared to Blue Cross’s ($500,000 gross charges * 46.5% of charges) $232,500. That’s a rate gap of $62,527, which would net a BlueCard vendor around $12.5K in revenue, assuming a 20% contingency take.

The gap gets even larger for more extreme cases. Given a 4-week hospital stay that generates $1.5M in gross charges, Regence would reimburse ($1,500,000 gross charges * 17% of charges) $255,000 compared to Blue Cross’s ($1,500,000 gross charges * 46.5% of charges) $697,500. Here the gap balloons to $442,500, which yields $88.5K in revenue at 20% contingency.

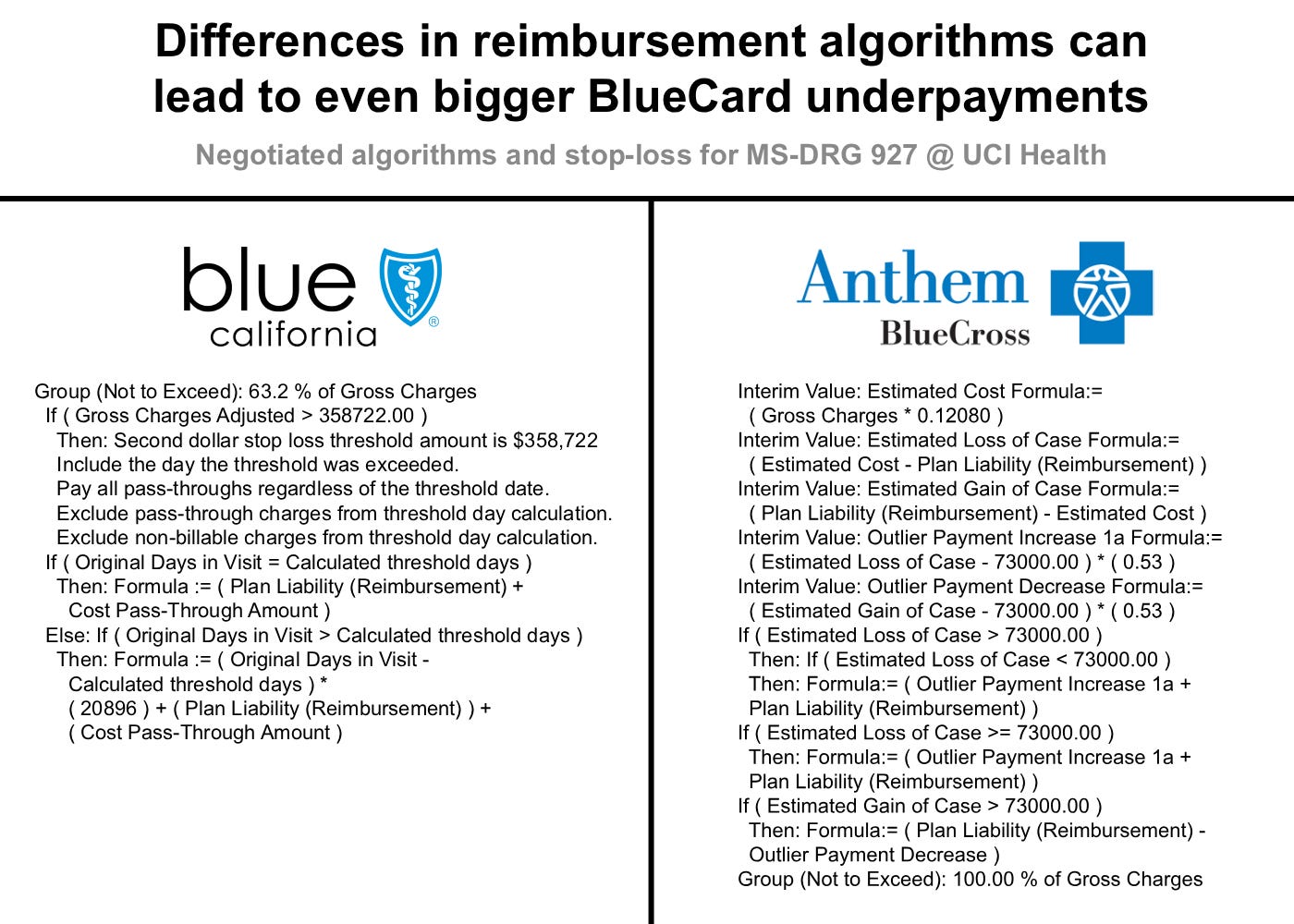

And the gaps can be even bigger for super complex care. Burns, for example, typically have their own negotiated reimbursement algorithm and a stop-loss clause. UCI Health in Orange, CA is one of about 125 burn centers in the United States. Here are their reimbursement algorithms for burns:

Not exactly straightforward. In the simplest possible case, if we take the California median gross charge of $1,771,782 for this billing code and assume we hit the max allowable % of charges for each payer, then the gap between them would be a massive $652,016. That’s $130K in revenue for a BlueCard vendor at 20% contingency (and $522K extra for UCI Health).

Realistically, accurately pricing these large claims requires genuine expertise and effort – you need to not only perfectly follow each payment algorithm and stop-loss formula, but also know each payer’s policies around what will be covered and reimbursed. Priced correctly, these claim gaps would probably be much smaller. Indeed, the largest gap I’ve actually heard of was around $300K on a long NICU stay.

That said, the juice is worth the squeeze. Find just a few of these big claims and you’re set for the year. Stack enough of them together and you end up with revenue upwards of $10M/year from BlueCard underpayments alone.

How did we get here?

BlueCard underpayments are a symptom of the complexity of U.S. healthcare. Their existence stems from the tangled history of the Blues, the accumulated complexity of the healthcare revenue cycle, and the constant need for providers to find revenue.

Historically, Blue Cross and Blue Shield were separate entities, each with their own purpose and national association. In 1982, the separate Blue Cross and Blue Shield associations merged, forming the modern BCBSA and licensing model (which permits one Blue per state). Over time, most separate state-level Blues merged or dissolved.

The remaining states with multiple Blues are artifacts of history. They either had separate Blue Cross and Blue Shield companies that never merged (California, Idaho, Washington), or had multiple regional plans that remained distinct (Pennsylvania, New York, Missouri, etc.). When BlueCard arrived in 1994, those unmerged Blues became seeds for the underpayment arbitrage that sprang up 20+ years later.

Over those same decades, the healthcare industry grew at a staggering rate, and administrative complexity grew with it. New regulations, new codes, CMS guidance, the ACA, the No Surprises Act, the OBBB, and more have all congealed into a thick regulatory soup. Payers and providers are locked in an everlasting war, writing increasingly complicated contracts designed to give themselves the upper hand.

The result is a system without design, full of independent, rational actors that can't stop to consider the whole. Each payer negotiates its own fee schedules, case rates, per diems, carve-outs, and percent-of-charges clauses. They adopt different bundling rules, clinical policies, stop-loss formulas, and claims processes. Before federal price transparency rules, even the Blues were effectively completely independent – they couldn’t see each other’s negotiated rates. Now that prices are public, the gaps and inefficiencies are clear, embarrassing, and easier than ever to exploit.

Meanwhile, most providers are just trying to survive. Public rates are tight and commercial rates are constantly pressed down by payers. Labor and capital costs are ever-increasing. And the federal government seems intent on cuts and policy changes. In this environment, providers use whatever means they have to eke out revenue and staunch the bleeding. If a vendor promises them essentially free, no-risk extra money, then they’re going to take it, ethics of rebilling be damned.

Put all this together and it’s easy to see why BlueCard underpayment vendors exist. The complexity of this ecosystem, grown over decades and thick with regulations and self-interested big players, creates seams and gaps which get filled by opportunists, eager to capitalize on that complexity. BlueCard vendors are hardly alone in this. Hundreds of other small players now inhabit this world, searching for any niche where they can make money.

The problem is that all those players have a vested interest in the continuation of the system that feeds them. For most vendors, complexity isn’t a problem to be solved; it’s their business model, the thing that gives them both the opportunity and reason to exist. A simpler system would both lower the barriers to entry (e.g. domain knowledge) and remove niches for them to fill, so most vendors will advocate for the status quo.

BlueCard vendors fit this mold perfectly. They’re the bottom-feeders of the healthcare ecosystem, getting fat on the detritus of the Blue whales above them. They’ll continue to thrive until someone actually puts in the work to simplify contracting and close the gaps between Blues.

What’s next?

Fortunately, change does seem to be happening, albeit slowly and incrementally. Last October, the BCBSA settled a massive, $2.8B anti-trust case focused on the BlueCard program and competition across states. Under the settlement, the BCBSA agreed to implement a long list of reforms to BlueCard focused on transparency, timeliness, and administrative costs. There’s nothing specifically about BlueCard underpayments, but many of the changes will probably indirectly reduce the attack surface for such arbitrage.

Further, some BlueCard vendors are improving their own processes and trying to reduce complexity. Specifically, they’re moving from retrospectively rebilling closed claims to proactively monitoring charges in real-time. That means providers are now just billing the higher payer up front, no rebilling needed.

As for the broader healthcare system, things are at the very least becoming more transparent. The 2021 Price Transparency rule and follow-up Transparency in Coverage mandate made healthcare prices publicly available for the first time. That pricing data is the source of this post, and it’s incredibly useful for shining a light on things like BlueCard underpayments. But illuminating and fixing aren’t the same thing. Price transparency lets us see the problems, but the immense complexity of the U.S. healthcare system continues to foster opportunities for difficult-to-detect exploitation and arbitrage. The hard work of simplifying it - closing loopholes and replacing systems - is just beginning.

FAQs

What is the scale of this industry?

It’s hard to say. There’s essentially no information about BlueCard underpayments online, and I couldn’t get anyone from one of the Blues to talk to me about it (and not for lack of trying). Backing out the exact amount of money being made here (or a count of claims rebilled) is nearly impossible, as the BlueCard rebilling process varies from state to state and isn’t associated with any specific CARC/RARC code.

Why don’t the Blues do something about this?

Some have. At least a few have disallowed this sort of BlueCard rebilling. Others, like Blue Shield of California, have claims routing tools seemingly intended to prevent BlueCard issues. I’m guessing that for most Blues, this issue is just small enough relative to their usual business that it doesn’t warrant special attention.

Why don’t providers just bill the higher price up front?

Due to the sheer complexity of medical billing/coding/contracting, providers often don’t know the exact dollar amount they’ll be reimbursed for a complex claim. That means they also don’t know which Blue will pay out more. Sometimes providers may have a general sense of which Blue reimburses more for a specific service line (e.g. inpatient surgery gets higher rates from Blue Shield) and bill accordingly. All that said, the BlueCard vendors themselves are increasingly moving to a proactive approach, where they help providers pick the higher Blue payer before filing a claim.

Is the cost of a BlueCard underpayment really passed on to the patient?

It depends. If the patient has insurance with high cost sharing (high deductible, coinsurance, out-of-pocket max, etc.), then they absolutely could be saddled with the extra cost of changing to the higher-reimbursing payer. In practice however, many BlueCard underpayment claims are for high-cost care, meaning the patient is likely to have already met their cost share obligations. Additionally, some providers will write off the difference in the patient’s cost share when switching to the higher-reimbursing payer.

Who are the BlueCard vendors?

Although it would be funny to call them out, I don’t like naming names for a piece like this. Plus, some of them were nice enough to chat with me for this piece.

How do I know if I’m affected?

If you travel to or live in a state with two Blues and have Blue insurance from a different state, you could be affected by this. As a patient, you’ll probably never know this even happened, you’ll just get a larger-than-the-counterfactual EOB/bill in the mail.

Some large, national employers have access to a Second Blue Bid from a Blue outside their state.

Nikhil Krishnan pointed me here and now I can’t leave. I need to get into BlueCard arbitrage

Super interesting article