The 340B program has gone off the rails

An Illinois case study of one federal program’s unchecked growth and unintended consequences

Key points

The 340B Drug Pricing Program isn’t working as intended. What started as a way to subsidize safety-net hospitals has become a critical way for many hospitals to generate income.

If the road to hell is paved with good intentions, then the 340B Drug Pricing Program must cover a mile-long stretch.

What started as a way to subsidize safety-net hospitals and help low-income patients has morphed into a critical way for hospitals to generate income. The program lets hospitals buy drugs at a discount, give them to patients, and then get reimbursed at a much higher price, pocketing the difference.

In theory, those profits are supposed to be passed on to patients – used to provide uncompensated care, offer community benefits, expand care access, and/or subsidize otherwise unprofitable lines of business. However, the program doesn’t require hospitals to report their 340B-derived spending, or even how much they make from the sales.

The unchecked nature of the program has resulted in numerous scandals. And its rapid growth in the past few years has started to garner attention. Mark Cuban tweeted about it, the Senate majority released a massive report on its problems, and industry leaders are calling it out.

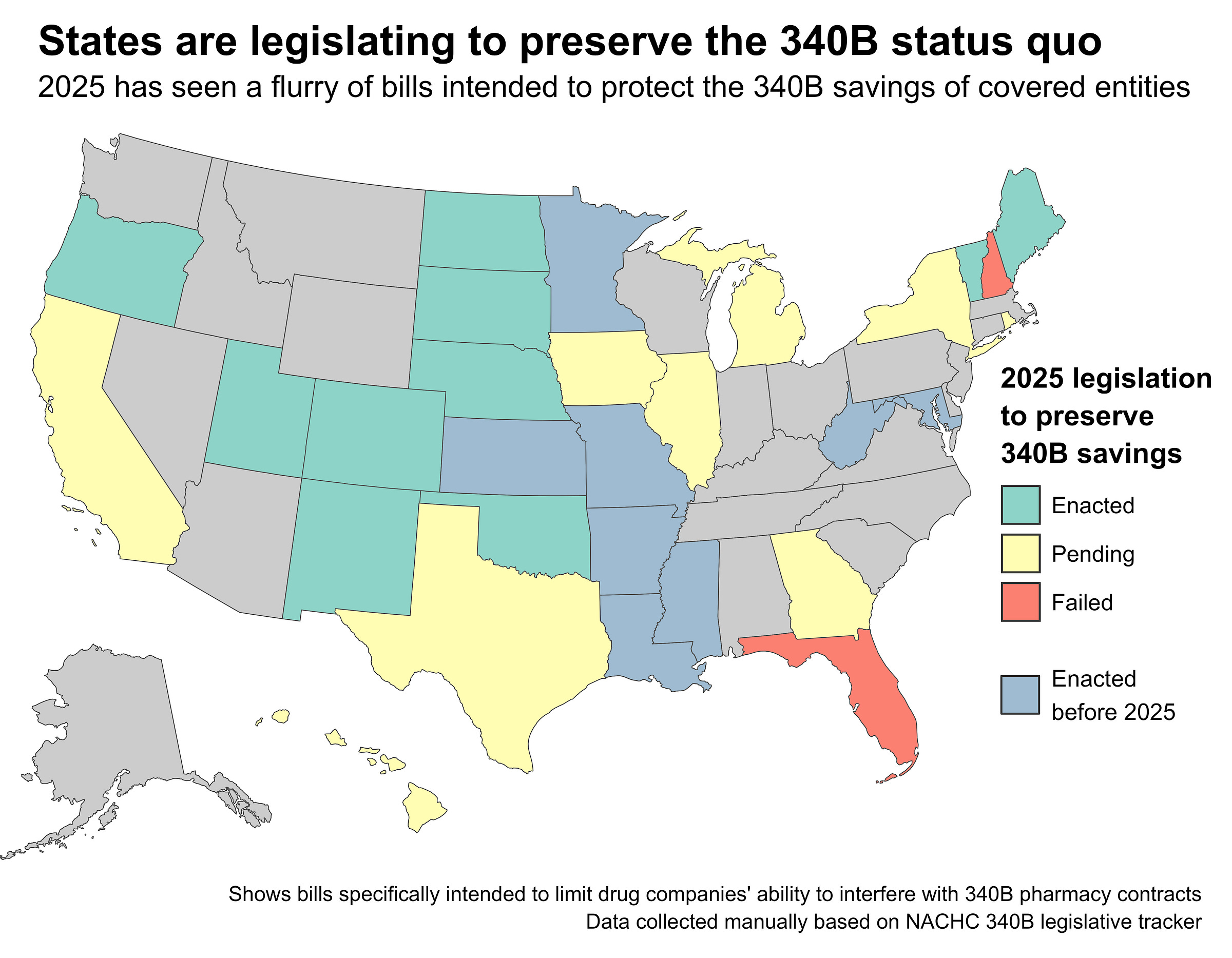

Meanwhile, drug companies, hospitals, and states are in an all-out legislative war. In 2020, drug companies began adding new restrictions and requirements to try to limit the scale of the 340B program. Hospitals responded by lobbying states to pass 340B contract pharmacy protection laws. Eighteen states to date have done so, and at least nine additional states had pending legislation in 2025 designed to preserve 340B profits for hospitals.

One of those states was Illinois, where legislators were considering SB2385 and HB3350. This pair of bills would have effectively stopped drugmakers from restricting 340B drug discounts, netting Illinois hospitals hundreds of millions of dollars. Yet the bills got curiously little attention outside of the business press, and there’s been essentially no public analysis or due diligence covering them.

So let’s fix that and take a hard look at 340B in Illinois. This post is a state-level effort to quantify the extreme growth of the program, identify winners and losers, and ultimately catalog 340B’s many unintended consequences.

It’s also a rebuttal to some of 340B’s critics. The program may be flawed and opaque, but many providers genuinely depend on it for survival. With already thin margins and no better alternatives, hospitals treat 340B as a necessary subsidy. Participation isn’t about opportunism; it’s often a rational response to structural underfunding and a broken system of incentives.

To understand how we got here - and why so many providers feel stuck - we’ll start with some background on the 340B program, then look at Illinois specifically, and finally take a look toward 340B’s future.

What is 340B?

The 340B Drug Pricing Program lets qualified health care providers, known as covered entities, buy drugs from manufacturers at a deep discount. Covered entities then sell those drugs to patients or their insurers at a higher price – usually the existing cash or negotiated rate.

The stated goal of the 340B statute is to enable covered entities, “to stretch scarce Federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.” But the actual intent is somewhat ambiguous. Are covered entities supposed to pass on their discounts directly to patients? Provide free care for uninsured patients? Invest in otherwise unprofitable lines of business? The law doesn’t specify, so providers are free to do whatever they want with their 340B savings.

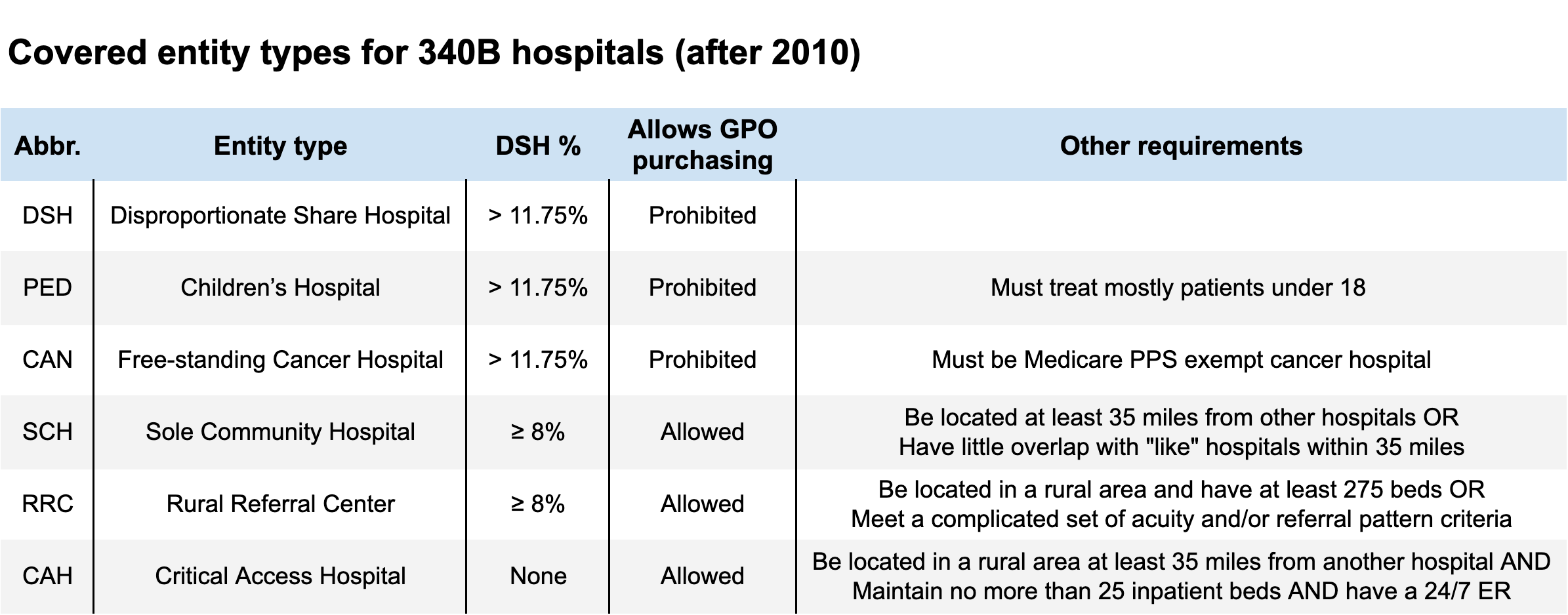

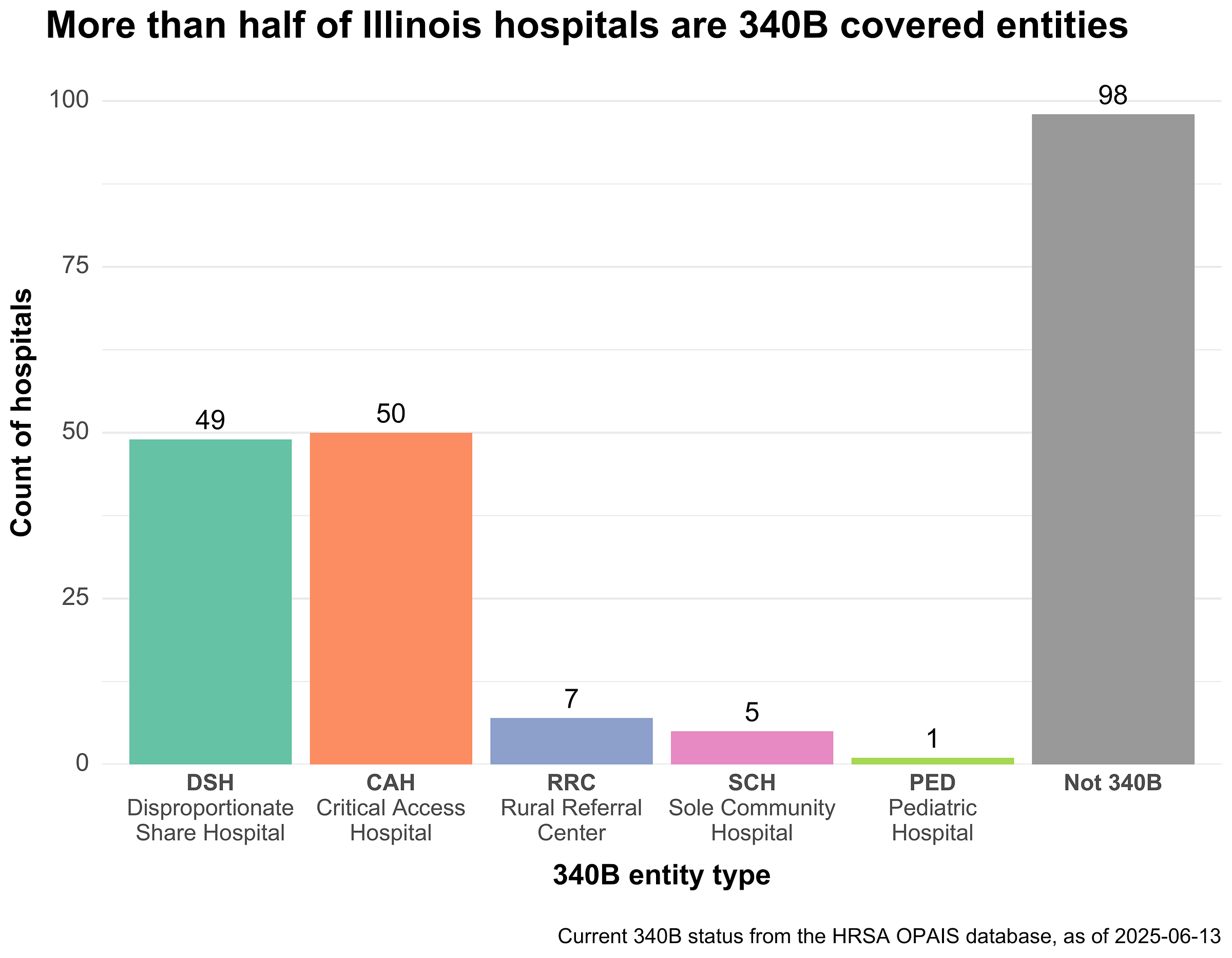

To participate in 340B, covered entities must be a federal grantee or one of six hospital types. The vast majority of the program is made up of just two hospital types: Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSH) and Critical Access Hospitals (CAH). DSHs must be nonprofit or government-run and have a certain percentage (11.75%) of their total inpatient days come from low-income patients. CAHs must be nonprofit or government-run but don’t have the same DSH percentage requirement.

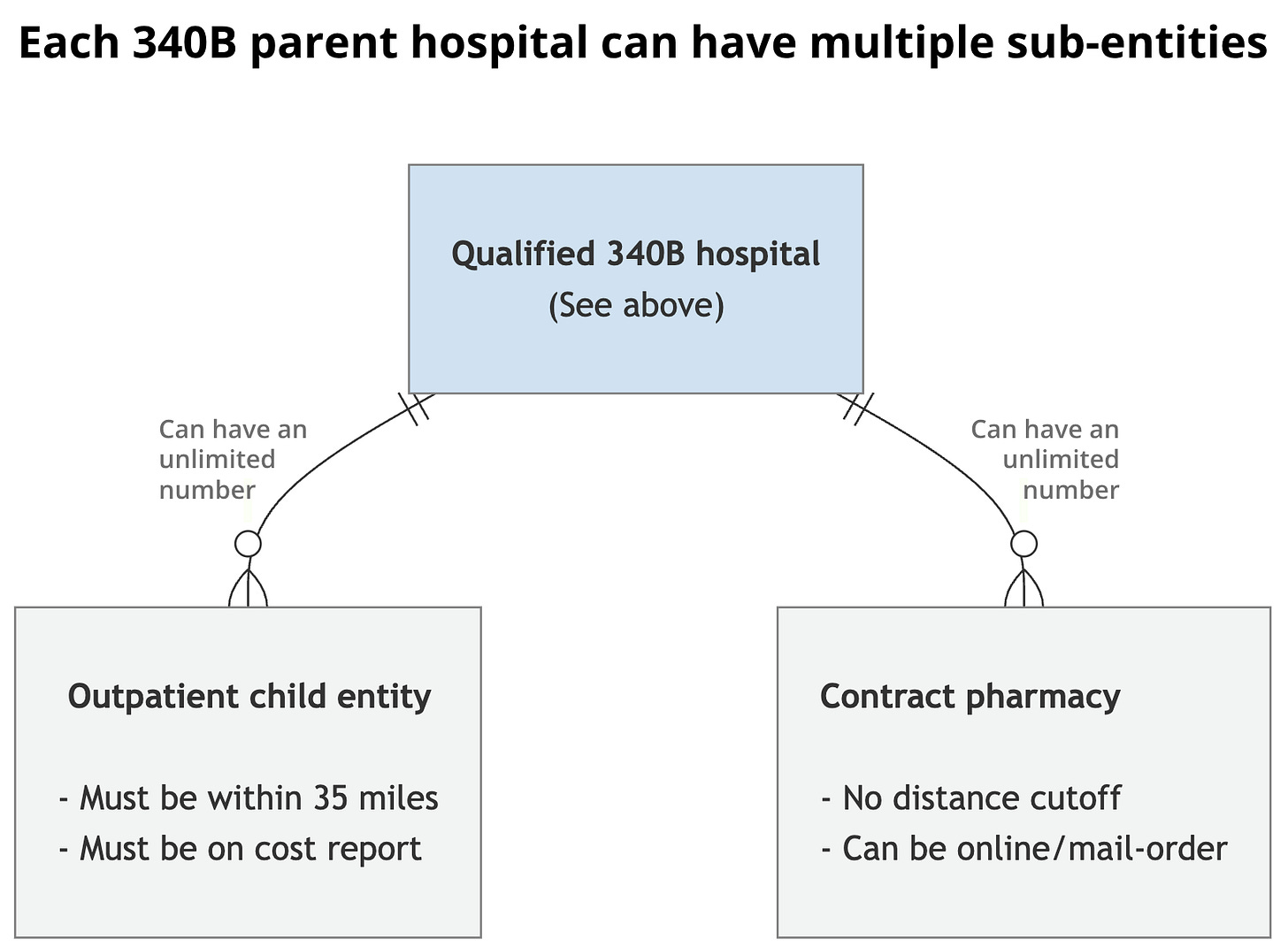

Qualified hospitals can also register off-site outpatient clinics as “child sites” of the main parent hospital. These child sites also qualify for 340B and can purchase and administer discounted outpatient drugs. Child sites must appear as reimbursable outpatient departments on the parent hospital’s Medicare cost report, but otherwise there are few restrictions on what qualifies. Most child sites are things like oncology centers, specialty clinics, and family medicine centers.

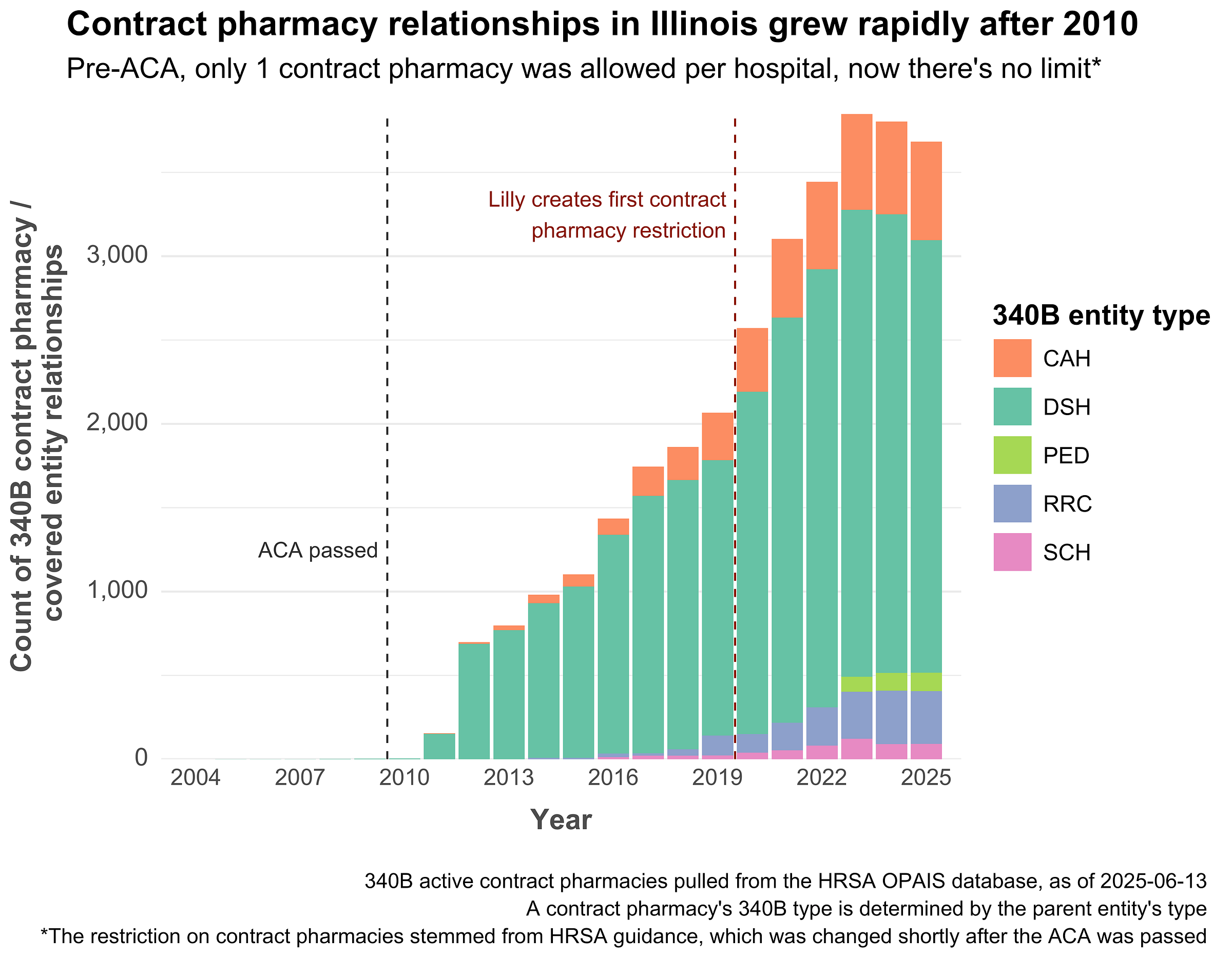

In addition to child sites, 340B covered entities can also dispense discounted drugs at both in-house and contract (external) pharmacies. Up until 2010, each hospital was limited to just a single contract pharmacy, but guidance changes after the passage of the ACA lifted that restriction, allowing an unlimited number. Contract pharmacies typically take a small cut of each 340B-eligible prescription and/or charge an administrative fee.

340B discounts don’t extend to every drug. Inpatient-administered drugs are entirely excluded, as are vaccines, OTC drugs, and some orphan drugs. 340B-purchased drugs must be separated (virtually or physically) from non-340B drugs of the same type. Calculating the 340B discount amount is complex, and the resulting discounted prices aren’t public. CMS estimates the average discount is somewhere around 35%, but others put it much higher.

Since the 340B discount rate is (usually) a fixed percentage, higher-cost drugs yield more savings for covered entities. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), which oversees 340B, publishes aggregate sales figures showing that the largest 340B purchases are for high-cost specialty drugs for conditions like cancer and HIV.

Finally, to participate in 340B, providers must prevent duplicate discounts and diversion. Duplicate discounts occur when a manufacturer provides a 340B discount and Medicaid rebate for the same prescription. Diversion occurs when a provider sells 340B-discounted drugs to someone who doesn't qualify as their patient. Drug manufacturers claim both these mechanisms are ripe for abuse.

How 340B pricing actually works

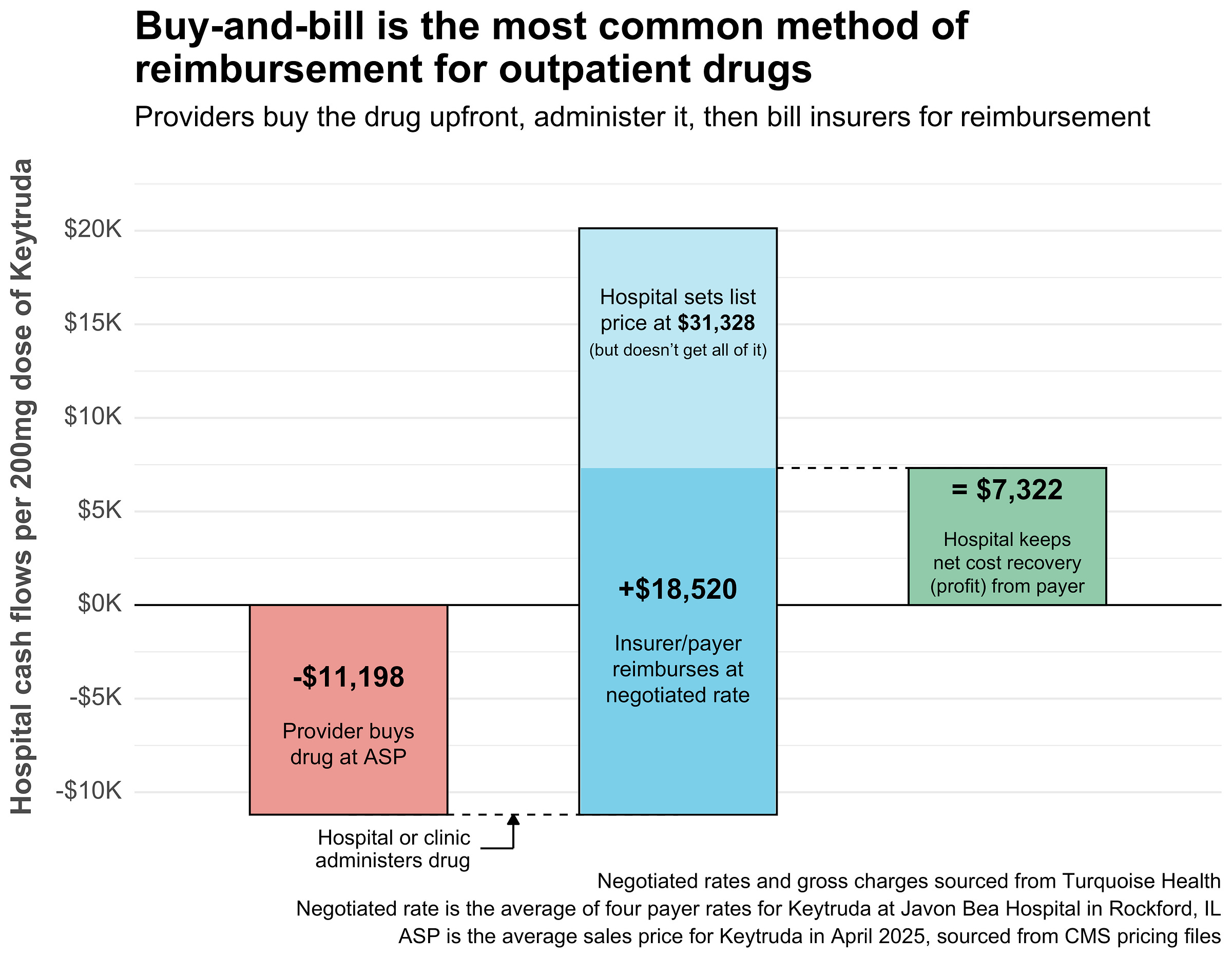

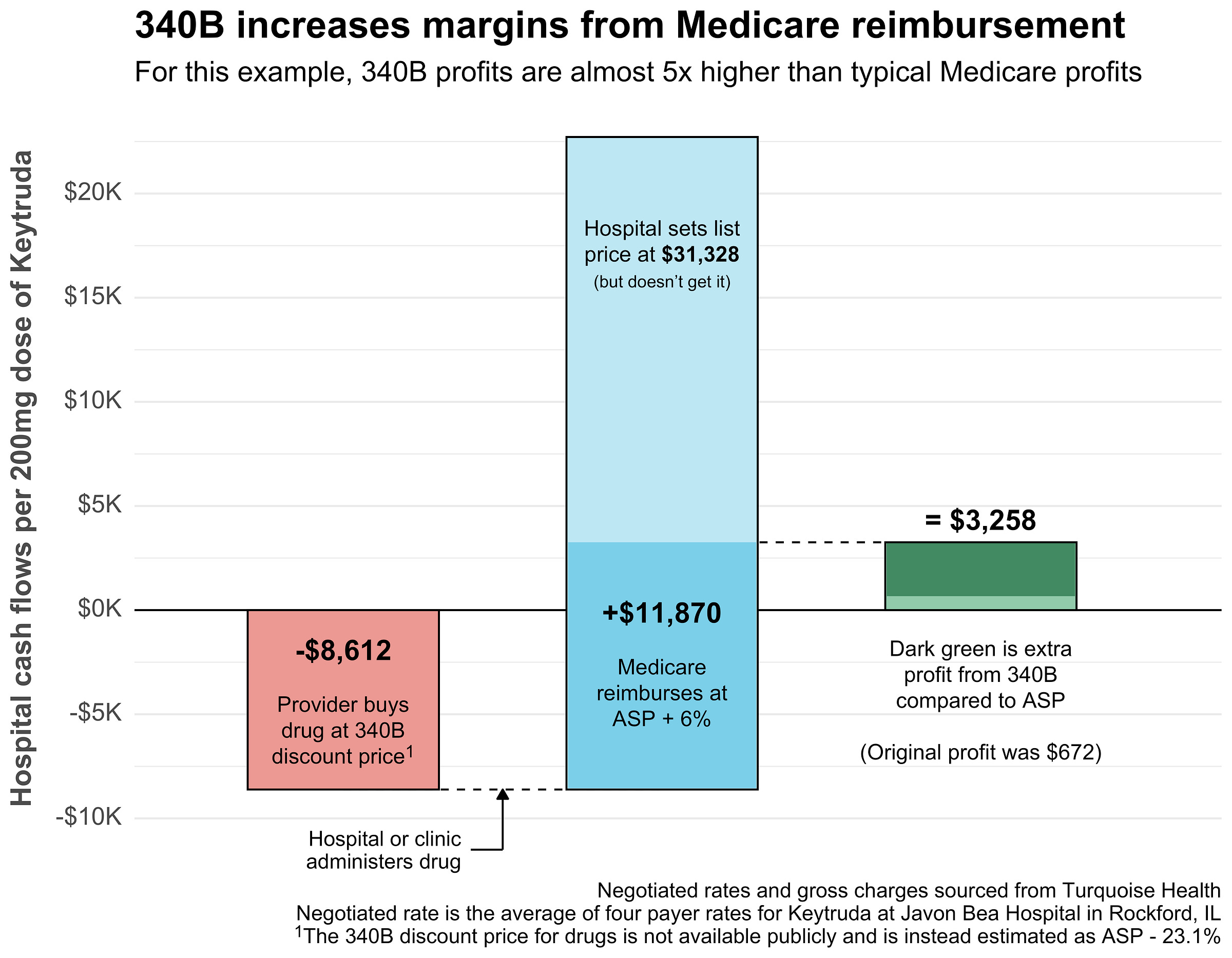

Before diving further into the 340B program in Illinois, let’s walk through a quick example to see how 340B actually benefits a covered entity.

Below are real prices for the cancer drug Keytruda at Javon Bea Hospital in Rockford, IL. In the standard (non-340B) case, Javon Bea likely practices what’s called buy-and-bill:

They buy the drug from a specialty distributor for somewhere close to the Average Sale Price (ASP). In this case, Keytruda is $11,198 for a 200 mg dose.

Next they administer the Keytruda to a patient. The patient has commercial insurance, which reimburses the hospital at a negotiated rate of $18,520 for the dose.

The hospital makes $7,322 ($18,520 - $11,198). Not all of that is profit. There are costs associated with the handling, administration, and storage of each dose.

In the end, the hospital gets something close to $7,322 in profit from a single Keytruda dose when reimbursed via standard buy-and-bill. Now let’s see what happens in the 340B case:

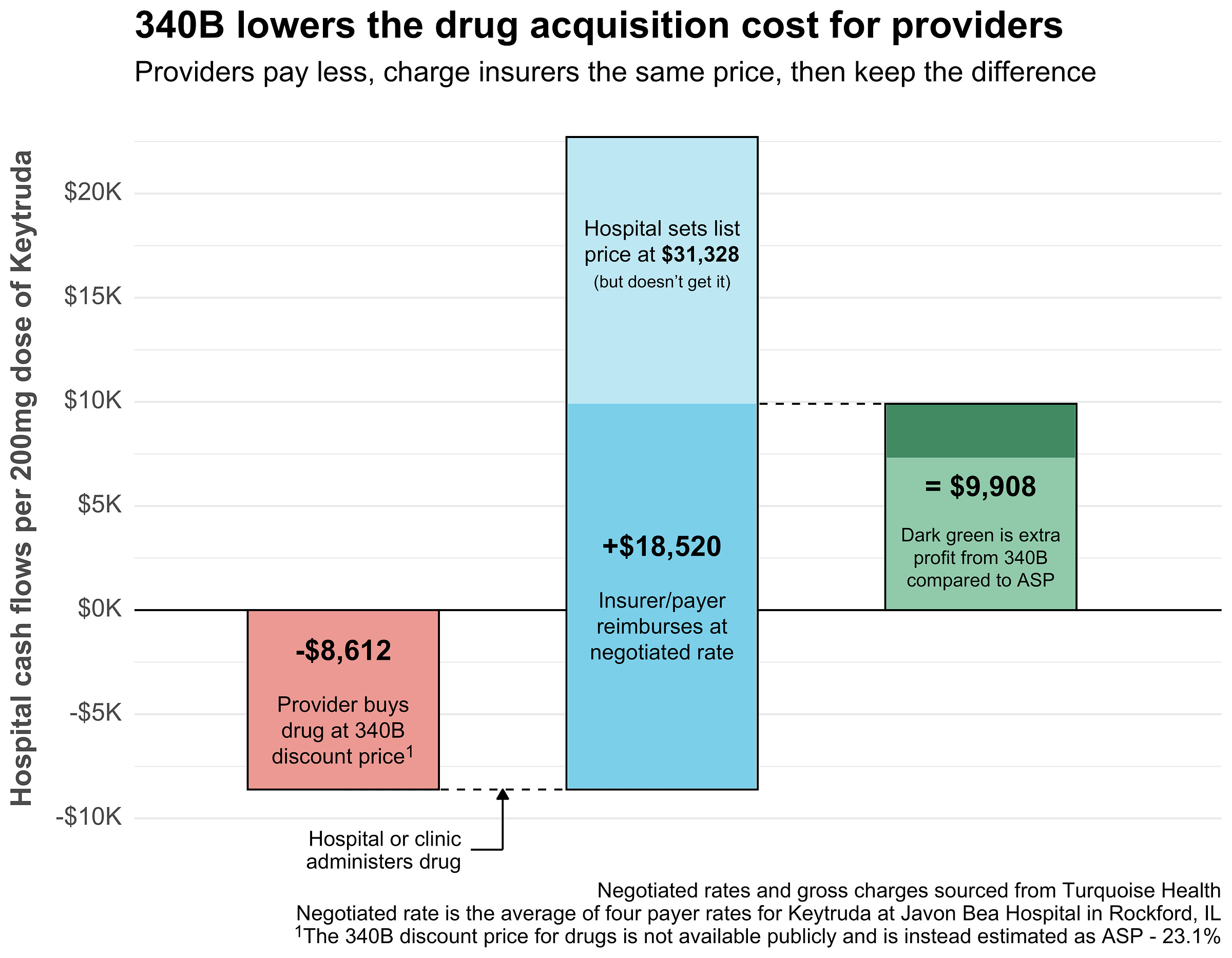

Javon Bea, a 340B covered entity, buys the same 200 mg Keytruda dose at a discount. Here the discount is estimated at -23.1%, but it’s likely much higher. In this case, they save at least $2,586 (original price - discounted price) via 340B pricing.

They administer the drug and bill the patient’s insurance. The negotiated rate stays the same at $18,520 for the dose.

The hospital now makes $9,908, with the $2,586 in acquisition cost savings getting added directly to their profits.

So, under 340B pricing, one dose of one drug for one patient netted Javon Bea an extra $2,586 in profit. Add that up across thousands of doses, and you start to glimpse the importance of 340B for many hospitals.

But 340B covered entities aren’t limited to giving 340B drugs to patients with commercial insurance, they can also give them to publicly-insured patients under Medicare (and Medicaid, but it’s more complex). Let’s see how 340B impacts Medicare Part B patients:

Once again, Javon Bea gets the 340B-discounted Keytruda price of $8,612.

This time however, they administer Keytruda to a Medicare patient. Medicare reimburses at ASP ($11,198) plus 6%, so $11,870.

Since the reimbursement is so much lower than commercial insurance, the hospital makes much less ($3,258) despite the 340B discount. However, without the discount they would’ve made only $672, so 340B almost 5x’d their profit.

When serving Medicare patients, 340B pricing can be the difference between a hospital essentially breaking even and making a sustainable profit. In the past, CMS tried to lower the Medicare reimbursement rate for 340B drugs to ASP - 22.5%, roughly matching the minimum 340B discount. However, 340B covered entities objected strongly, and later won a Supreme Court case forcing CMS to reverse its decision in 2022.

Now, with some background on 340B and knowledge of how it works, let’s see how 340B has played out in Illinois.

340B is huge in Illinois

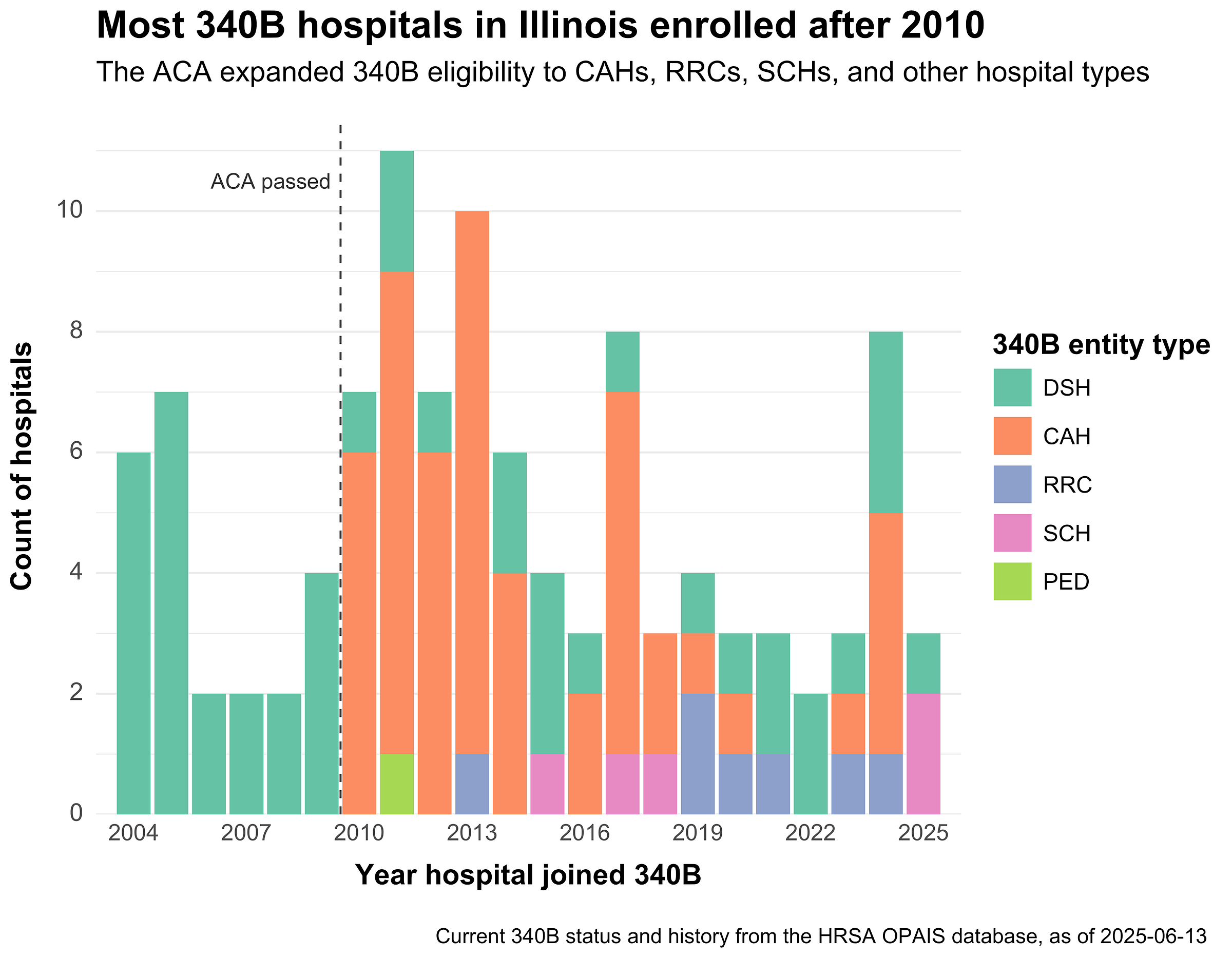

340B has grown rapidly in Illinois, from 34 participating hospitals in 2010 to 112 in 2025, an over 200% increase. Over half the hospitals in the state are now 340B covered entities.

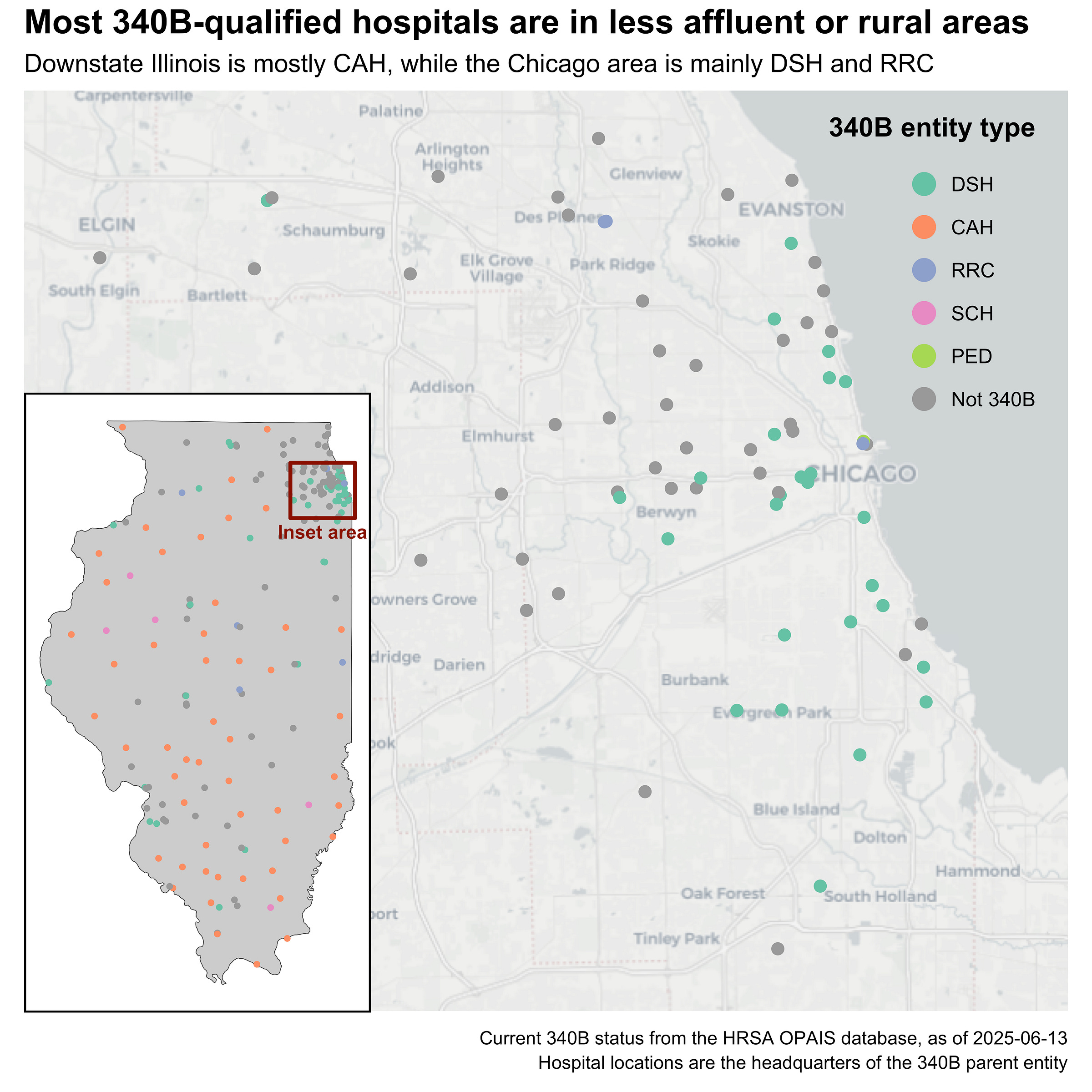

Of the six possible hospital types, Critical Access (CAH) and Disproportionate Share (DSH) are the most common, with CAH spread throughout rural parts of the state and DSH concentrated around Chicago. Broadly speaking, 340B hospitals tend to be located in less wealthy areas. However, their satellite clinics (i.e. child entities) often extend into wealthier areas to capture greater returns from commercially-insured clients.

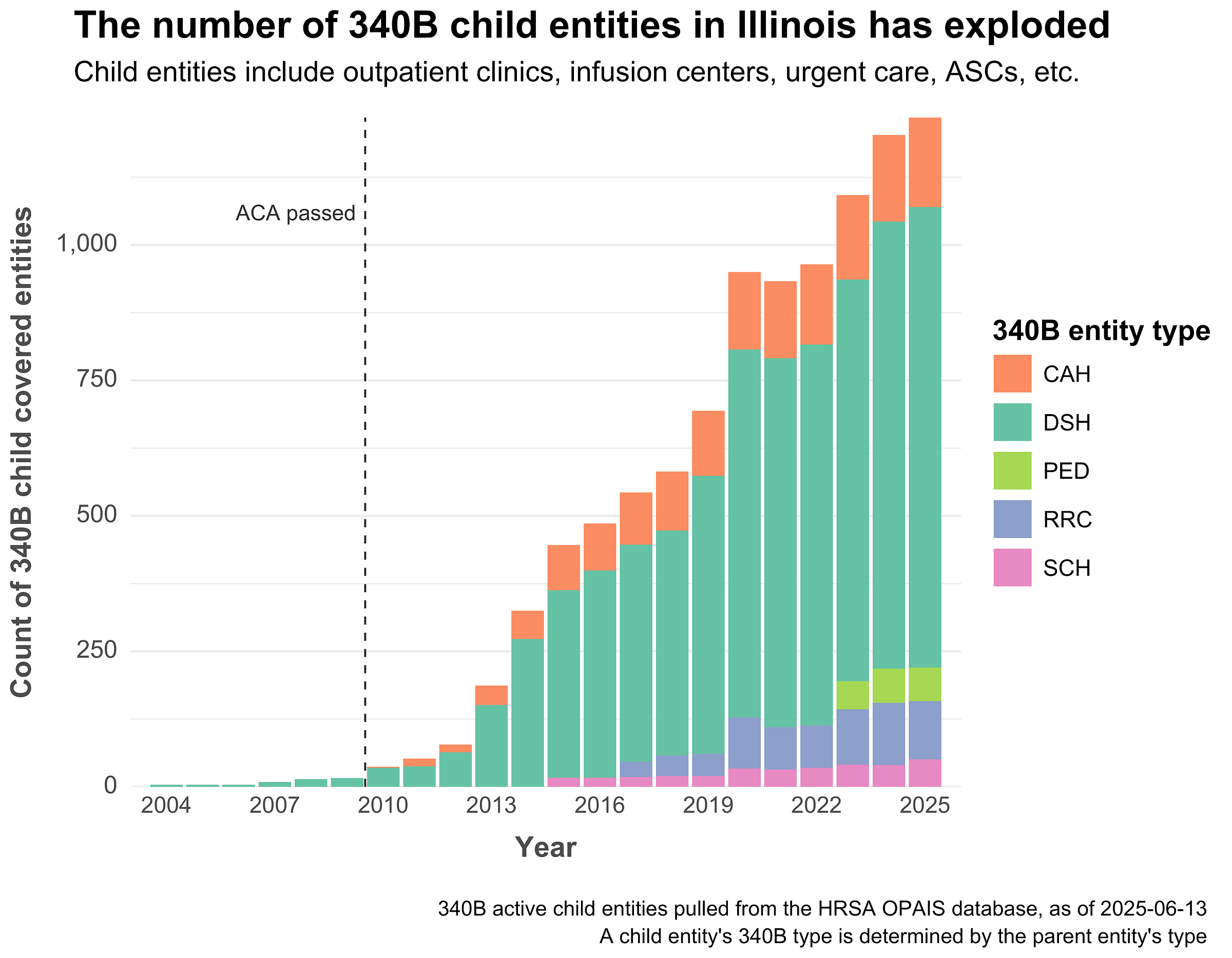

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded the 340B program to include four new hospital types: cancer hospitals, Rural Referral Centers (RRC), Critical Access Hospitals (CAH), and Sole Community Hospitals (SCH). The ACA also expanded state Medicaid programs, including in Illinois, which indirectly boosted 340B enrollment by raising hospital DSH percentages. Accordingly, the vast majority of Illinois hospitals joined after 2010:

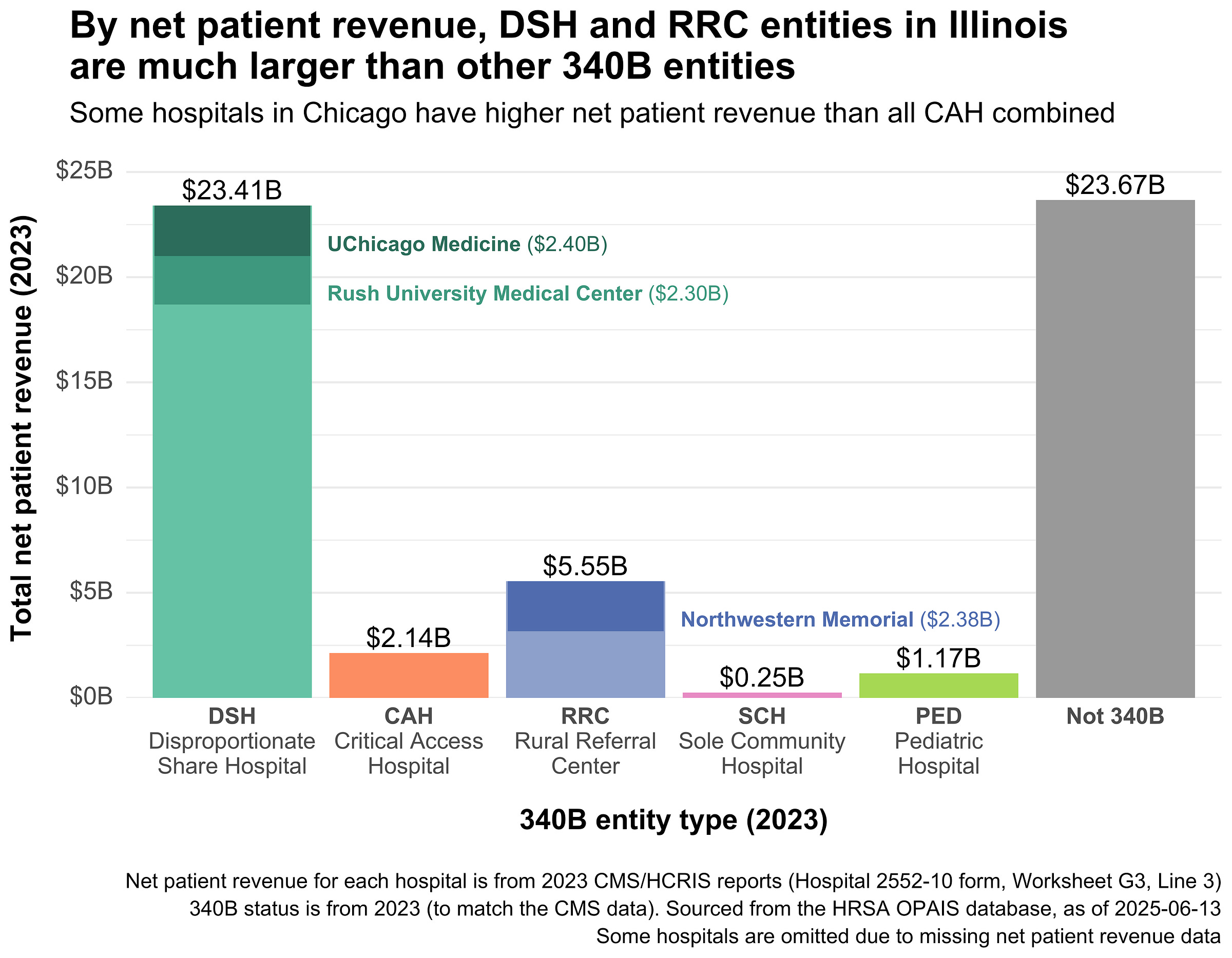

340B covered entities aren’t limited in size, so many of the largest hospitals in Illinois are now part of the program. Northwestern Memorial, Rush University Medical Center, and UChicago Medicine are all 340B covered entities. Each had more net patient revenue than all 50 CAHs in Illinois combined.

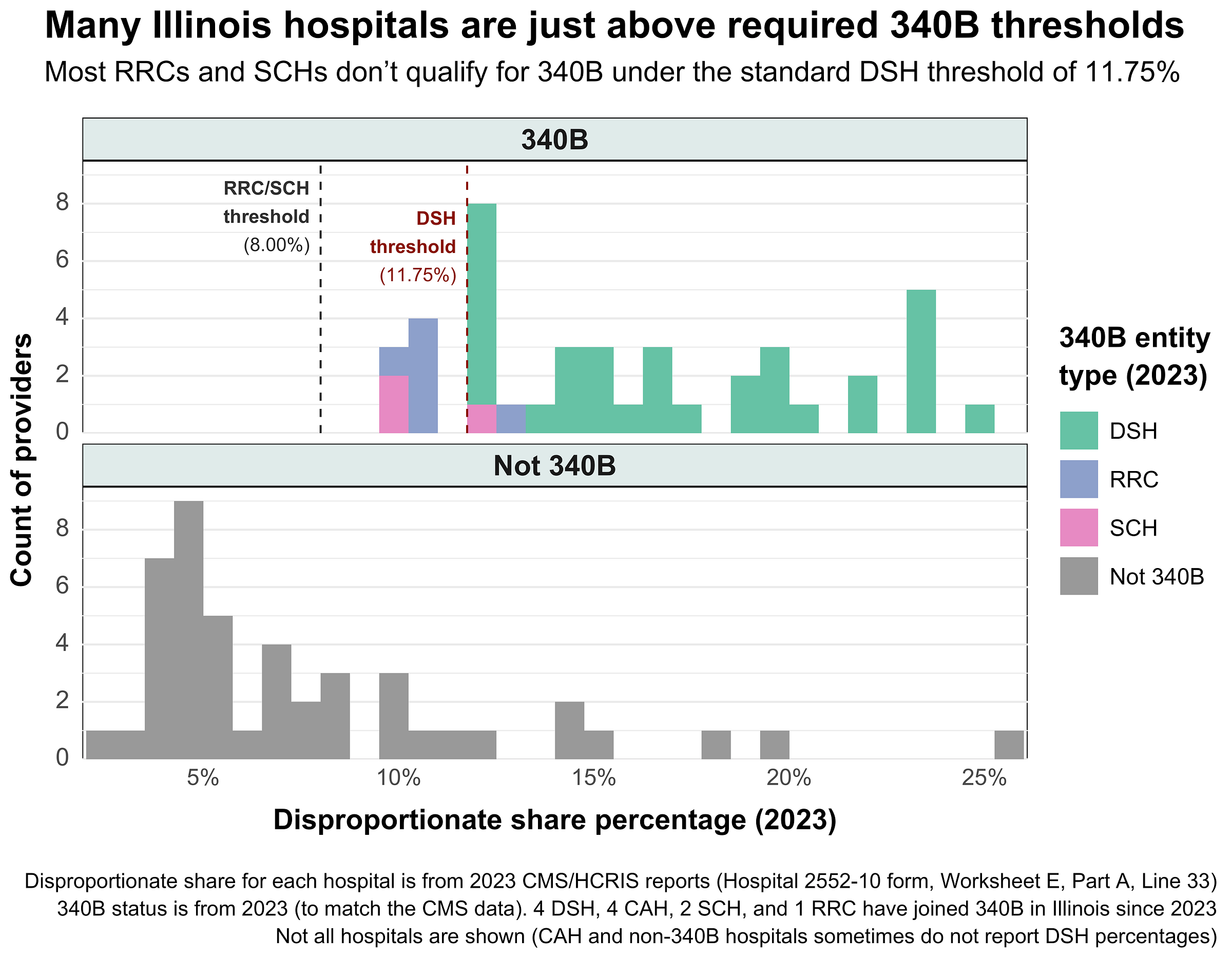

In order to qualify for 340B, a certain percentage of a hospital’s inpatient days must serve low-income patients. For DSH providers, the DSH percentage threshold is 11.75%. For RRCs and SCHs, the threshold is lower at 8%. Many Illinois 340B hospitals sit right above their respective DSH thresholds, indicating that they may take on just the required number of low-income patient days, but no more. Edit: Note that at least some of the hospitals just above the threshold have their DSH percentage adjustment capped at 12% by formula.

Other hospitals get themselves reclassified to qualify. In 2020, Northwestern Memorial was classified as a Rural Referral Center, even though it’s in the middle of downtown Chicago. Despite the name, Rural Referral Centers are not required to serve rural patients, only to have 275 inpatient beds. The lower RRC threshold of 8% allows Northwestern to qualify for 340B despite a DSH percentage of around 10%.

Illinois hospitals clearly see the value of the 340B program – the vast majority of those that qualify have now joined. And while the post-ACA growth in 340B hospital enrollment has tapered off, a new avenue for 340B growth has emerged.

340B child entities and contract pharmacies are everywhere

Each 340B hospital can have an unlimited number of child entities (CE) and contract pharmacies (CP), and both types of entities have grown immensely in Illinois.

Fifteen years ago, Illinois had around 25 total child entities. Now that number is close to 1,250, a 50x increase. The vast majority of those entities belong to large regional hospitals and DSH providers in the Chicago area, including Carle Foundation Hospital (110 CE), Javon Bea Hospital (92 CE), Loyola University Medical Center (93 CE), and Rush University Medical Center (75 CE).

Each child entity can administer and prescribe 340B drugs, expanding the parent hospital’s opportunities for savings. This has led to concerns about health system consolidation, as hospitals move to buy up community practices to expand their 340B networks and patient pools.

There are minimal limits (up to 35 miles, but sometimes more) on how far child entities can be from the parent hospital. As a result, a common approach to maximizing 340B profits involves opening satellite clinics in distant, well-off areas, using the parent hospital’s DSH status to qualify.

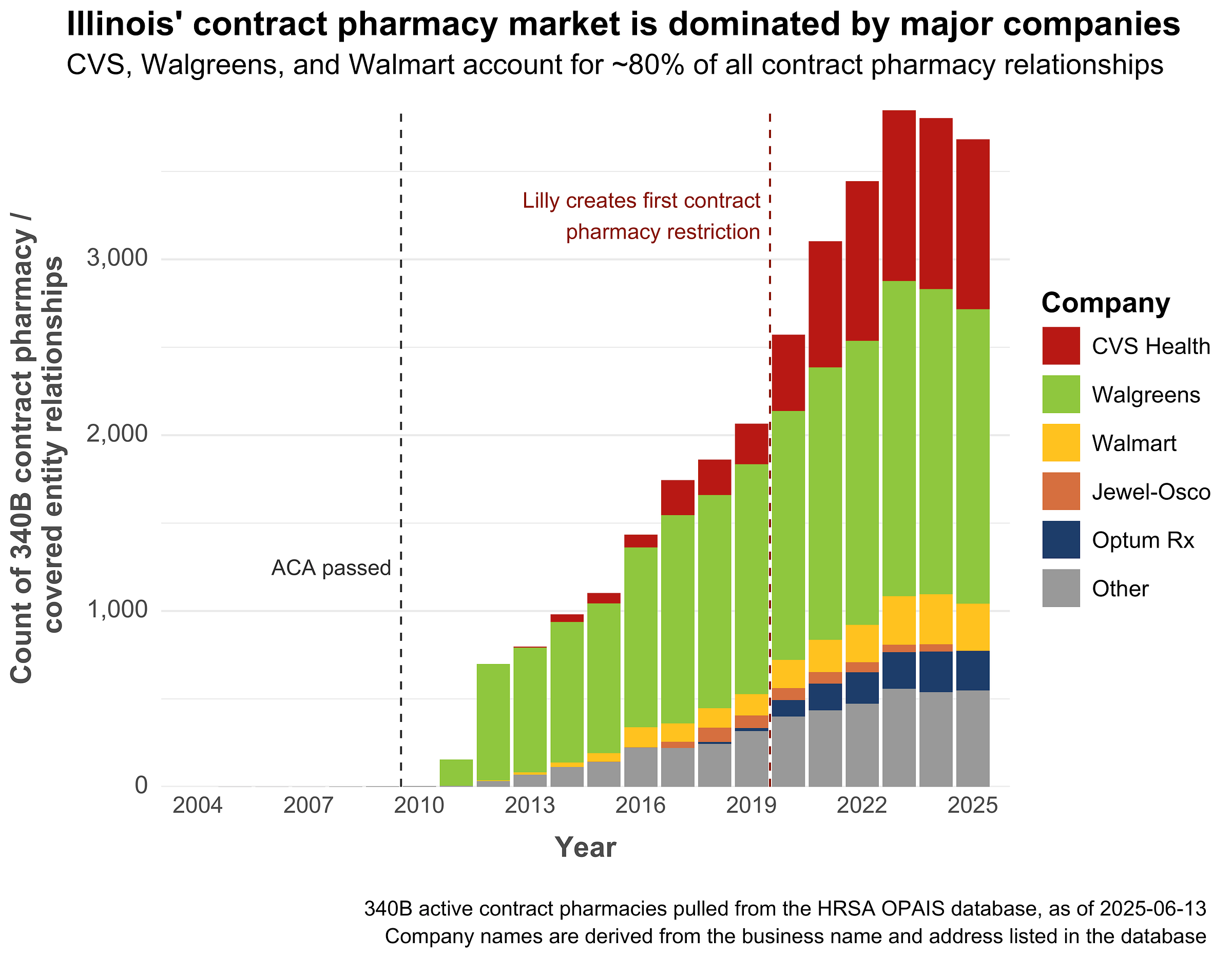

Contract pharmacies have grown rapidly as well. HRSA’s guidance change in the wake of the ACA had a profound effect on Illinois’ contract pharmacy market. In 2010, there were just 5 unique contract pharmacies in the entire state. By 2011, there were 155. And in early 2025, there were 1,243.

Each pharmacy can contract with more than one 340B hospital, so it’s useful to quantify contract pharmacy growth by the number of unique provider-pharmacy relationships. Here’s what that looks like for Illinois:

Since patients are largely unaware of and unaffected by the 340B status of their drugs, hospitals are incentivized to expand their contract pharmacy networks as much as possible. The wider the network, the more likely patients are to use it, which means more profits captured for the hospital. The three Illinois hospitals with the largest number of contract pharmacies are Rush University Medical Center (515 CP), Loyola University Medical Center (350 CP), and UChicago Medicine (290 CP).

Pharmacies themselves are incentivized to participate because they typically get a share of the 340B profits or a per-transaction dispensing fee. Many big-name pharmacies also run their own 340B third-party administrator (TPA), separate entities that manage 340B inventory on behalf of covered entities. For example, CVS owns Wellpartner, one of the largest 340B TPAs.

The growth of the contract pharmacy industry has prompted pushback from drugmakers, who have placed restrictions on 340B covered entities with the goal of limiting their discounts. Some manufacturers require 340B covered entities to designate a single contract pharmacy. Others require covered entities to submit detailed claims data, ostensibly to prevent duplicate discounts. These restrictions have generally been upheld in federal court, prompting states to create laws to protect the access of covered entities (such as Illinois SB2385 and HB3350).

Throughout the U.S. 340B contract pharmacy relationships are increasingly dominated by a few big companies. That’s also true in Illinois, where CVS and Walgreens are by far the largest players:

The reduction in contract pharmacy relationships since 2023 seems to be the result of pharmacy closures, mostly among Walgreens and grocery-store pharmacies like Kroger (Mariano’s) and Jewel-Osco.

Who benefits most from 340B in Illinois?

So, 340B has grown massively in Illinois. Now that it’s big, who benefits the most?

To find out, we’d ideally want to compare the actual 340B drug profits of each Illinois hospital. However, those numbers aren’t public and they’re nearly impossible to estimate using public data.

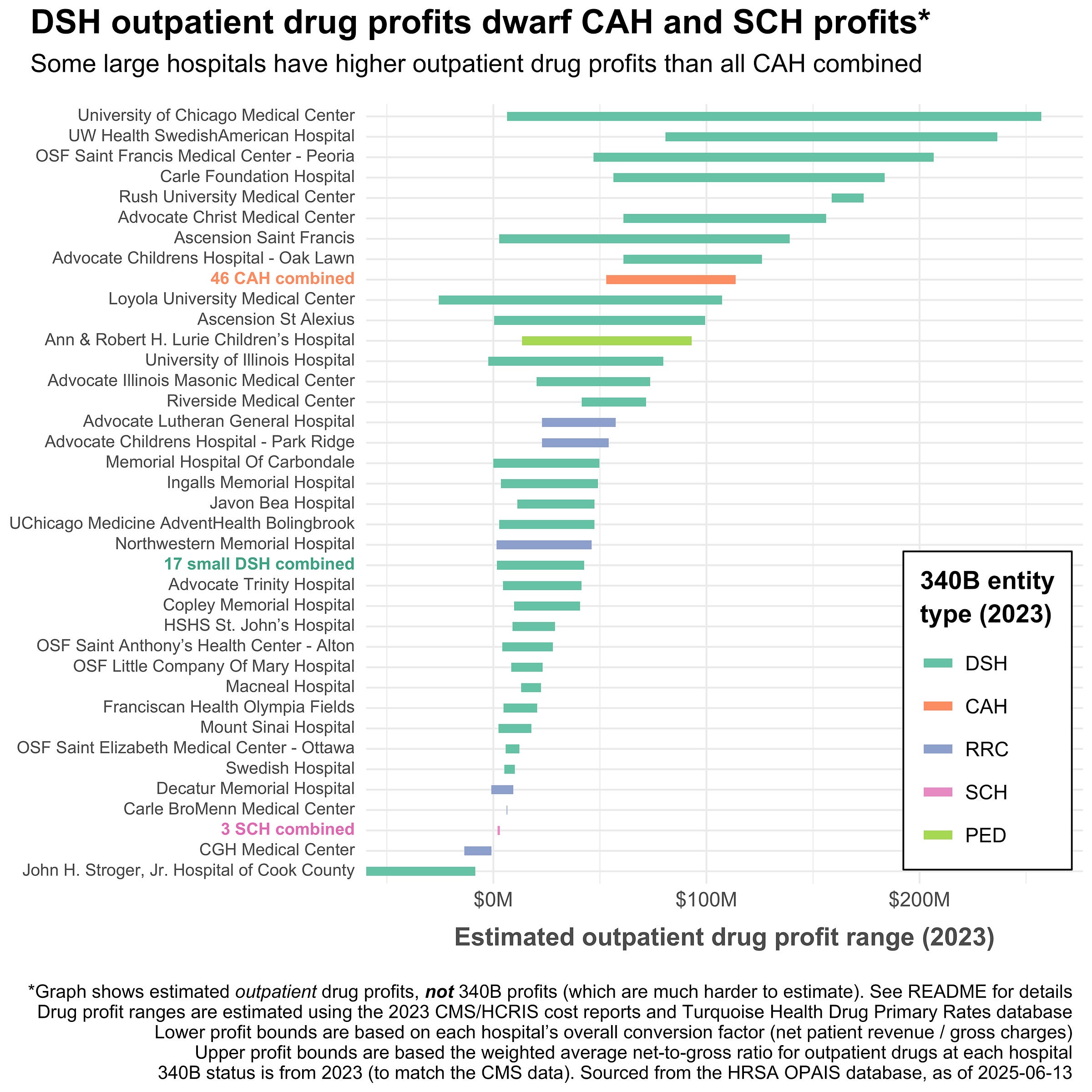

Instead, we can estimate the overall outpatient drug profits of each hospital, a close proxy for 340B profits. The calculations are a little bit complex and imperfect (see here for details), but the relative results are robust and clear – big academic medical centers (AMCs) and regional hospitals simply make way more money from outpatient drugs than smaller hospitals.

Part of that is simply scale, large hospitals just have more patients, larger outpatient networks, and more revenue than smaller ones. But part of it is also a focus on more complex care, which in the case of 340B, returns higher profits.

The plot below shows the range of likely outpatient drug profits per hospital. The lower bound of the range is based on the hospital’s overall conversion rate from their CMS cost report. The upper bound of the range is based on the hospital’s average gross-to-net ratio for common drug HCPCS.

Looking at Illinois, you can see that many AMCs and regional hospitals like OSF Saint Francis have higher outpatient drug profits than every CAH in the state combined. Whether or not you think this is bad depends on your beliefs about the intent of the 340B program.

A big part of public policy is fairly allocating limited resources. In the case of 340B in Illinois, a disproportionate and growing share of the benefits are going to large, well-capitalized health systems, not to the small, scrappy safety-net hospitals the program (probably) intended to support.

On the one hand, hospitals like OSF Saint Francis and UChicago Medicine really do serve a high number of low-income patients (the latter has one of the highest DSH percentages in Illinois). On the other hand, these large hospitals likely have the patient volume and finances to be sustainable without the subsidy of 340B. Further, 340B participation changes their incentives, pushing them to acquire outpatient practices and making them increasingly reliant on the profits from 340B drugs (see below).

Plus, the 340B program isn’t costless. It’s essentially a direct transfer from drug companies to hospitals. If pharma companies can’t make money on certain 340B drugs, then they’ll find other ways to generate profits. It’s like squeezing a balloon: the harder the collective 340B program is squeezing on one part, the more prices are likely to go up elsewhere – and having big hospitals participate in the program adds a lot of squeeze.

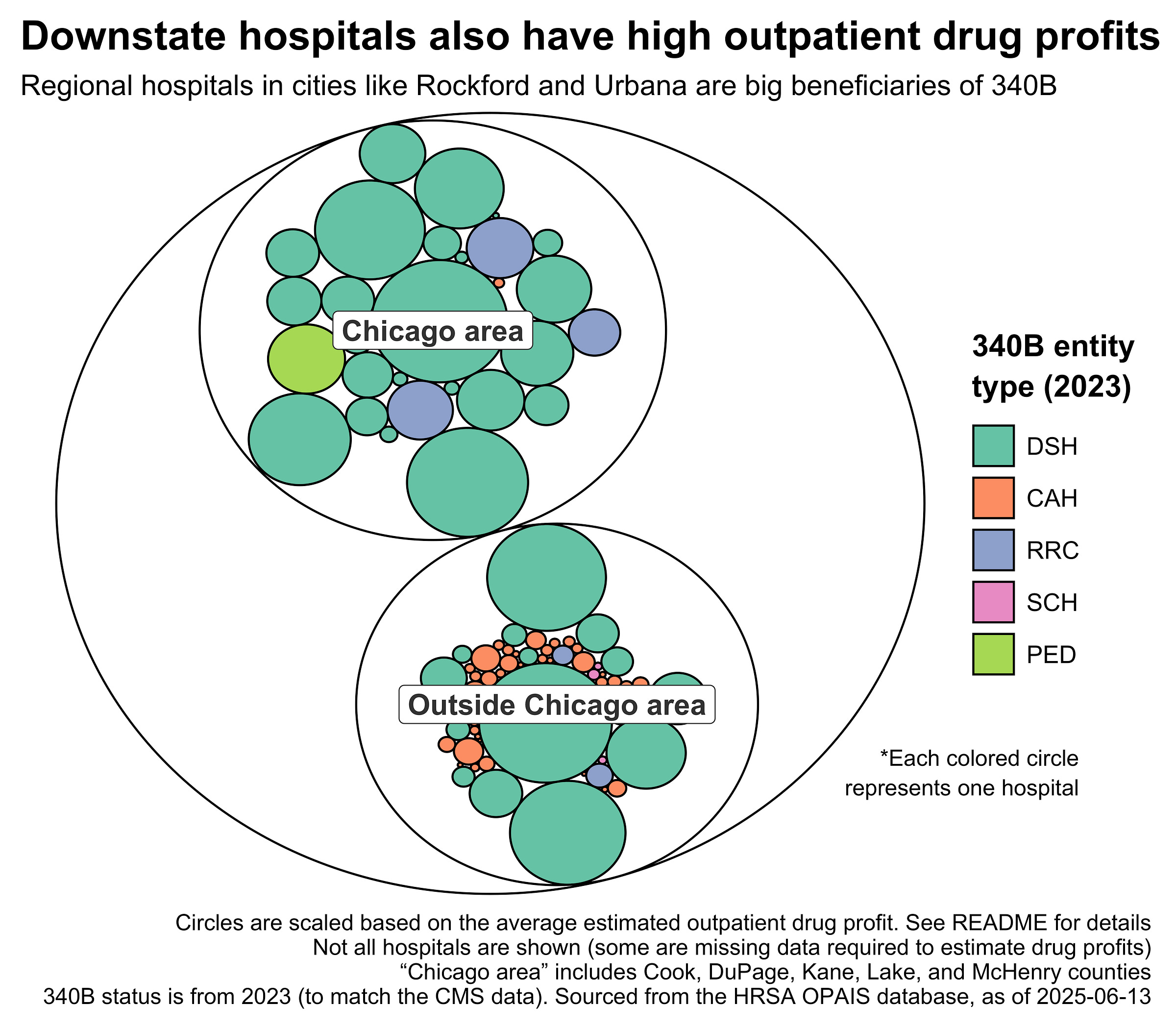

Looking at the plot above, you might get the impression that only big Chicago hospitals benefit from 340B, but that’s not the case. Here’s each hospital represented by a circle scaled to the midpoint of its estimated outpatient drug profits:

Regional hospitals in Peoria, Rockford, and Urbana-Champaign also participate in 340B. Insofar as these cities are regional hubs for Illinois and destinations for advanced care, it may be beneficial to subsidize their hospitals, even though they’re quite large.

This adds some nuance to the question of which hospitals the 340B program should help. Should 340B subsidize regional hospitals but not AMCs and big-city hospitals? Or should 340B only allow small, truly critical hospitals to participate? Such questions are critical but unanswered. HRSA’s deference to statute and unwillingness to look critically at 340B qualification criteria lets big hospitals run away with the ball.

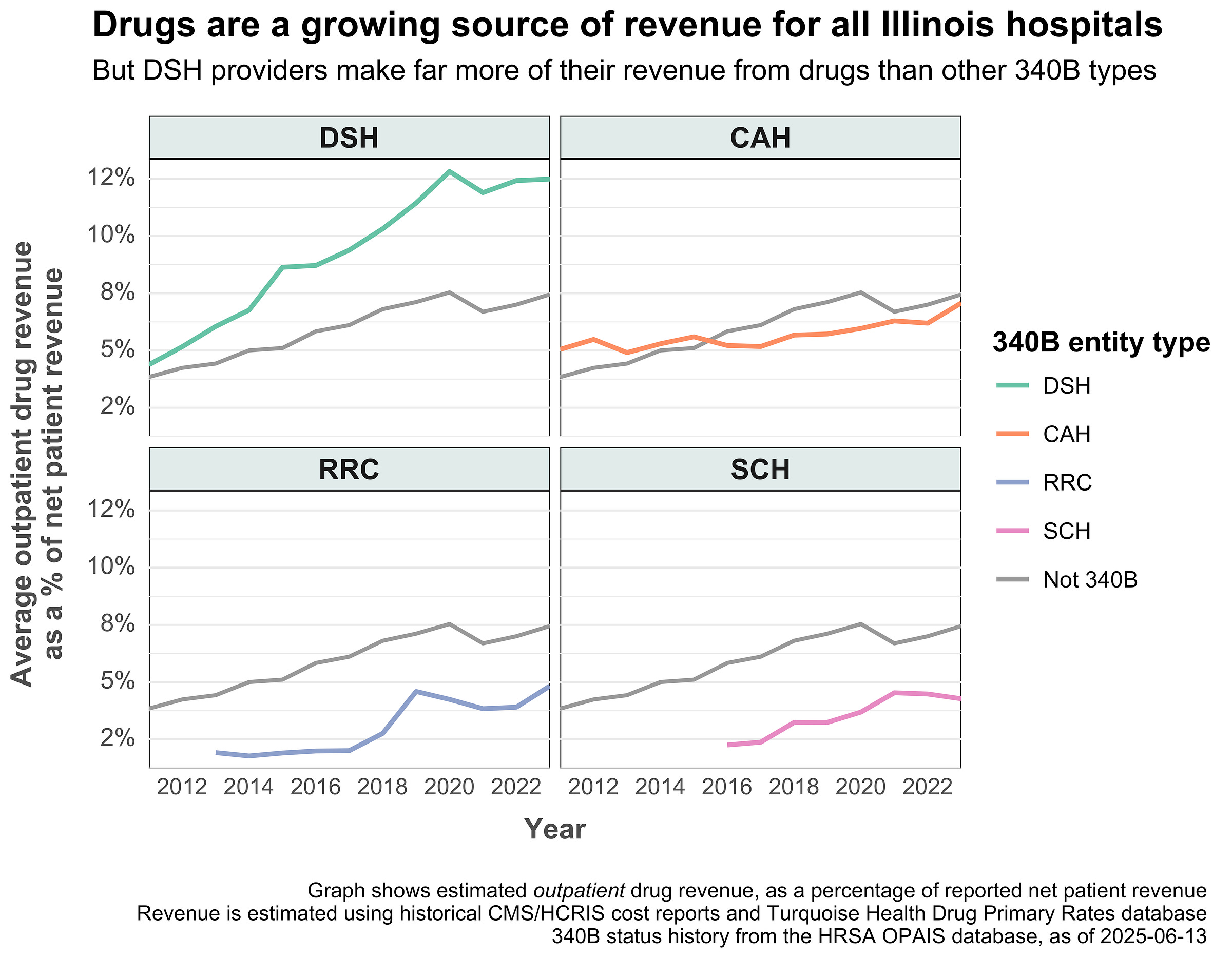

The result has been massive growth of the 340B program and, perhaps more dangerously, an increasing reliance on outpatient drugs as a source of income. The plot below shows the average proportion of net patient revenue stemming from outpatient drugs by hospital type:

The DSH average is clearly pulling away from the others, mostly driven by big providers in Chicago. Some hospitals drew close to 20% of their net patient revenue from outpatient drugs alone.

The exact cause of the increased drug share among DSH providers is hard to determine. Drug negotiated rates could be rising faster than negotiated rates for other types of care. Or perhaps prescription volume went up while negotiated rates remained static. Or maybe providers bought up existing outpatient practices and made them into child entities.

Whatever the reason, the 340B program seems to further increase hospitals’ reliance on outpatient drugs as a source of income. This increases their risk exposure to changes in the law and to restrictions from drugmakers. So far, hospitals have managed to insulate themselves from such changes via litigation and state-level laws, but a major shakeup of 340B would likely be disastrous for many of them.

What does 340B mean for Illinois patients?

To recap, 340B has grown a lot in Illinois and most of that growth has benefited large hospitals. But 340B is ostensibly about benefiting low-income patients, so presumably some of the savings get passed on to them via lower prices or free care, right?

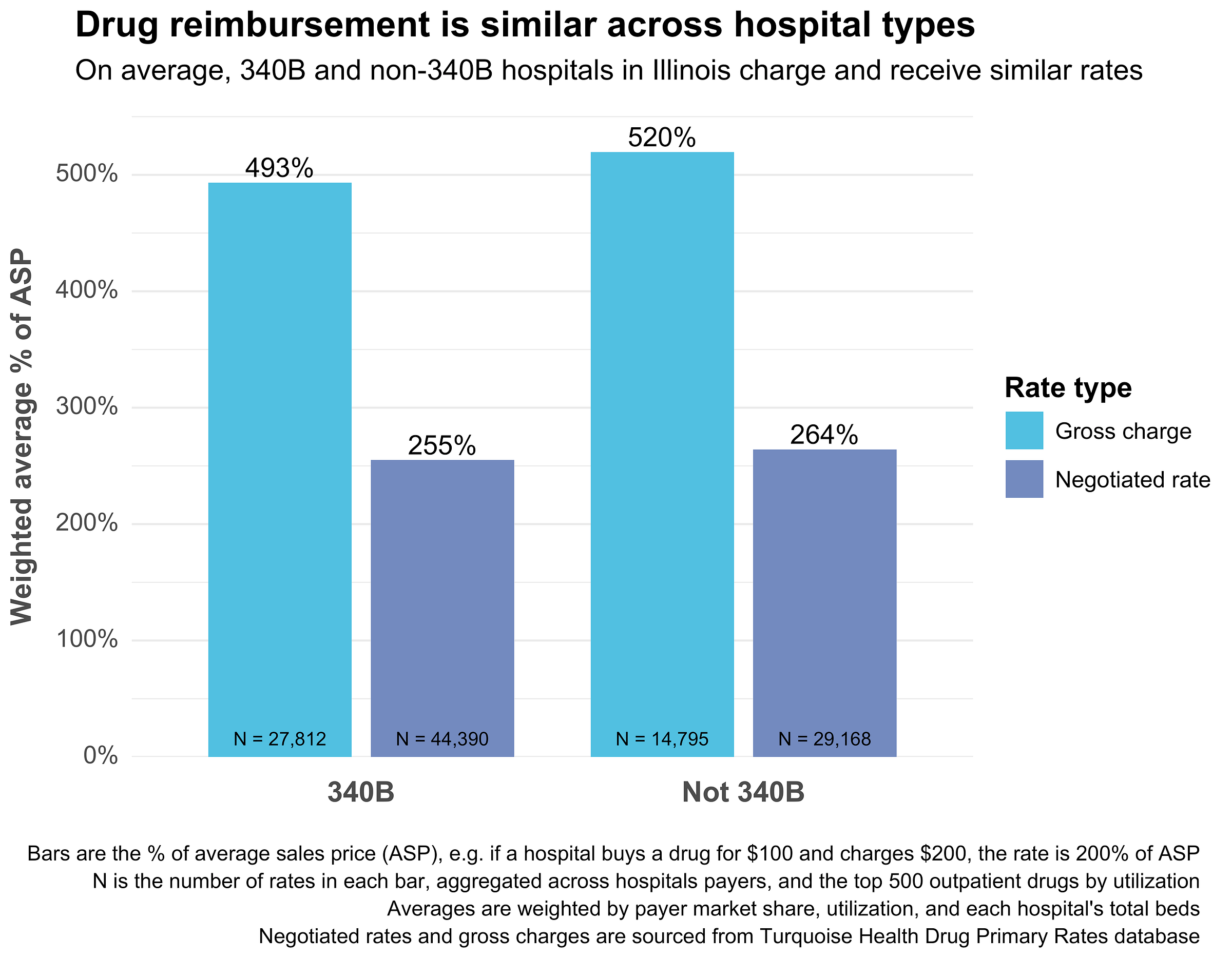

No, not really. At least not in a way that’s publicly visible. Illinois patients (or their insurers) pay basically identical drug prices across 340B and non-340B hospitals. That’s true state-wide and across many other cuts of the same pricing data (e.g. broken out by hospital size, drug indication, etc.). If 340B discounts are getting passed along to patients, it's through indirect means like medication assistance programs or free vaccinations, not through reduced rates.

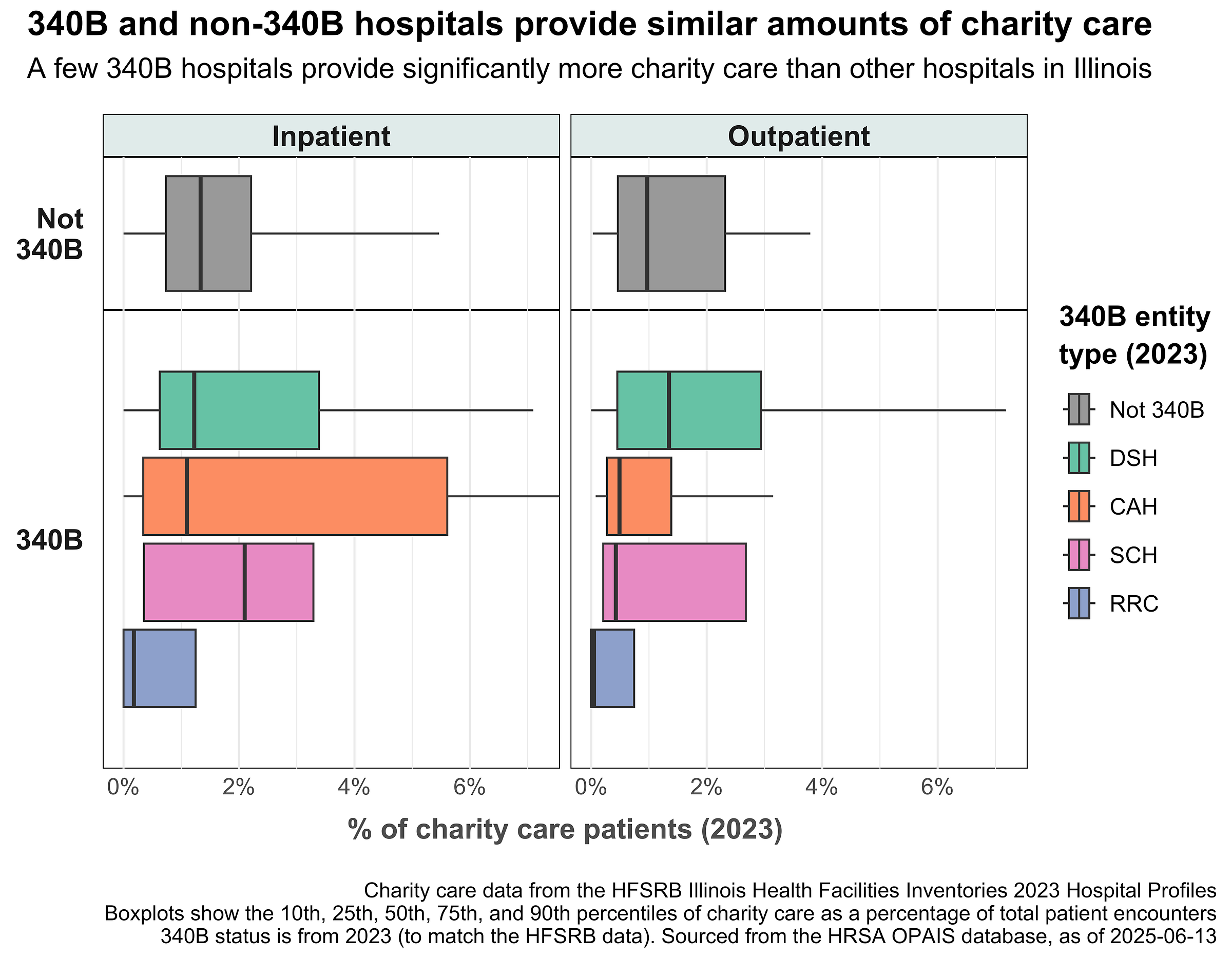

The same story is true for uncompensated care. On average, Illinois 340B hospitals treat only slightly more charity care cases than non-340B hospitals. They also don’t provide significantly more expensive charity care – their costs as a percentage of net revenue are just 0.3 percentage points higher.

There are some exceptions to this trend. Some 340B CAHs, such as Hammond-Henry Hospital, do seem to provide a significant amount of uncompensated care. Stroger Hospital is another unique case. It’s a publicly-owned DSH hospital with an extremely high disproportionate share percentage (~34%), a high proportion of charity care patients, and a drug cost-to-charge ratio (CCR) of around 0.64.

It’s very possible that 340B hospitals are using their savings to benefit patients in ways that are mostly invisible in public data. This could include subsidizing otherwise unprofitable service lines like obstetrics, creating new community health or outreach programs, or preventing a hospital closure.

However, none of these activities are obvious because the 340B program has no reporting requirements whatsoever. Hospitals don’t need to share what they did with their 340B profits, or even report how much 340B saved them. This lack of transparency has obscured 340B’s potentially good effects while cracking the door for attacks from drugmakers.

In sum, evidence of 340B’s benefit to patients is ambiguous at best. More data and transparency is needed to enable meaningful study of the program.

All aboard?

Many providers do use 340B savings for their intended purpose. However, the design of the 340B program itself encourages growth and invites malfeasance. Congress created an open-ended discount with no reporting requirements, and providers responded rationally by treating it as a general subsidy rather than a charity fund.

Now everyone is stuck with 340B. The growth of the program has made it self-sustaining, a FOMO-fueled money train running rampant through the U.S. healthcare system. Providers that are already on the train have a strong incentive to preserve its inertia. Many of them probably even depend on it to survive. Providers that aren’t yet on board know they’re leaving free money on the table.

Meanwhile, drug manufacturers are trying to hit the brakes. For the past 5 years, they’ve come up with a litany of restrictions to slow the program down. Most recently, they pulled some of the few levers left to them by limiting contract pharmacies to a single location and by switching to rebates instead of upfront discounts.

States have responded by legislating to protect 340B providers. In Illinois, SB2385 and HB3350 would prevent drugmakers from limiting contract pharmacies or collecting any data related to 340B. Other states have passed similar bills – here’s the legislative landscape as of June 2025:

For states, 340B is a way to bring out-of-state money into the state at no cost to taxpayers. Letting pharma companies restrict access is akin to leaving free money on the table, so states have responded rationally by blocking them.

All of this is to say that providers and states are largely trapped. Their most morally righteous move - to not engage with a program that has clearly grown beyond its original intent - is against their self-interest and probably against the interests of their patients. Forgoing 340B would mean forgoing millions in subsidies all while other hospitals and drug companies profit. It’s no wonder that providers do everything they can to leverage the program.

If anyone is to blame for the current state of 340B, it’s Congress and HRSA. They started the train, got it moving, then took their hands off the controls – abdicating their responsibility to tweak the program. Worse still, they turbocharged many of the program’s problems: adding unlimited contract pharmacies, weakening enrollment requirements, and ignoring the need for transparency. 340B may be broken, but it’s broken by design – everyone is acting in their own self-interest in the system of incentives Congress created.

What’s next for 340B?

The 340B program has gone off the rails. Its uncontrolled expansion has critically warped hospital incentives and finances, creating issues that will be difficult to undo without legislative intervention. In Illinois, outpatient drug revenue now makes up an increasing portion of DSH hospital revenue, and the number of child entities continues to multiply. This excessive dependence on 340B leaves hospitals vulnerable; a sudden federal shift, such as the One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB), could severely impact their margins or even their existence – more on that soon.

Congress and HRSA should take responsibility for the 340B program. A sensible reform plan would involve tightening eligibility criteria, demanding clear reporting on how savings benefit patients, and limiting contract pharmacy arrangements. These actions would require little federal spending and would start to rebuild the link between discounted drugs and the benefits the program was meant to deliver.